THE MAKING OF A MONEY SQUEEZE?

Some market participants are watching for cracks in U.S. money markets as echoes of 2019's funding shocks and worries about small and mid-size banks return. What's at stake?

Stocks reached new records in February as the U.S. Federal Reserve entered the home stretch of its two-year-long battle with inflation, having managed not to derail the economy with its rapid interest rate increases. But the mood has been more fitful in money markets of late.

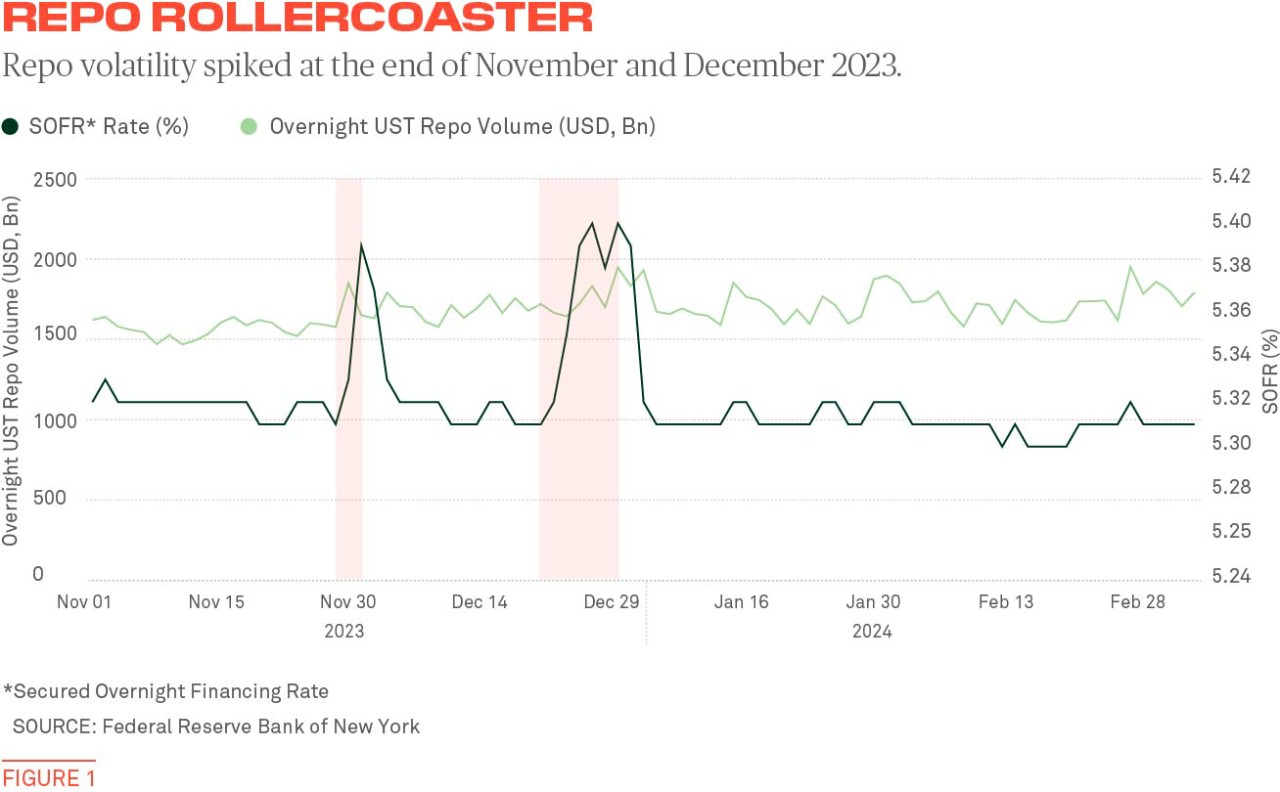

Echoes of 2019’s liquidity squeeze in overnight lending or “repo” markets and last March’s regional bank failures have unnerved some market participants, just as that soft landing seems within reach. The Fed is now thinking of slowing the pace of its quantitative tightening (QT) program–used to shrink its bond portfolio–to reduce the risk of sudden lurches in overnight funding rates.

The central bank is also trying to improve the attractiveness of some rarely used liquidity facilities at a time when regional banks’ sources of short-term funding are narrowing, and as negative headlines about commercial real estate loans rattle investors.

Repo markets haven’t suffered pronounced blips since December (see Figure 1), making some think there is no need for the Fed to slow down its balance sheet runoff any time soon. But the stakes remain high, especially as some are worried that small and mid-size banks may be bearing the brunt of unevenly distributed reserves in the banking system, or struggling to absorb the still-high costs of paying interest on customer deposits.

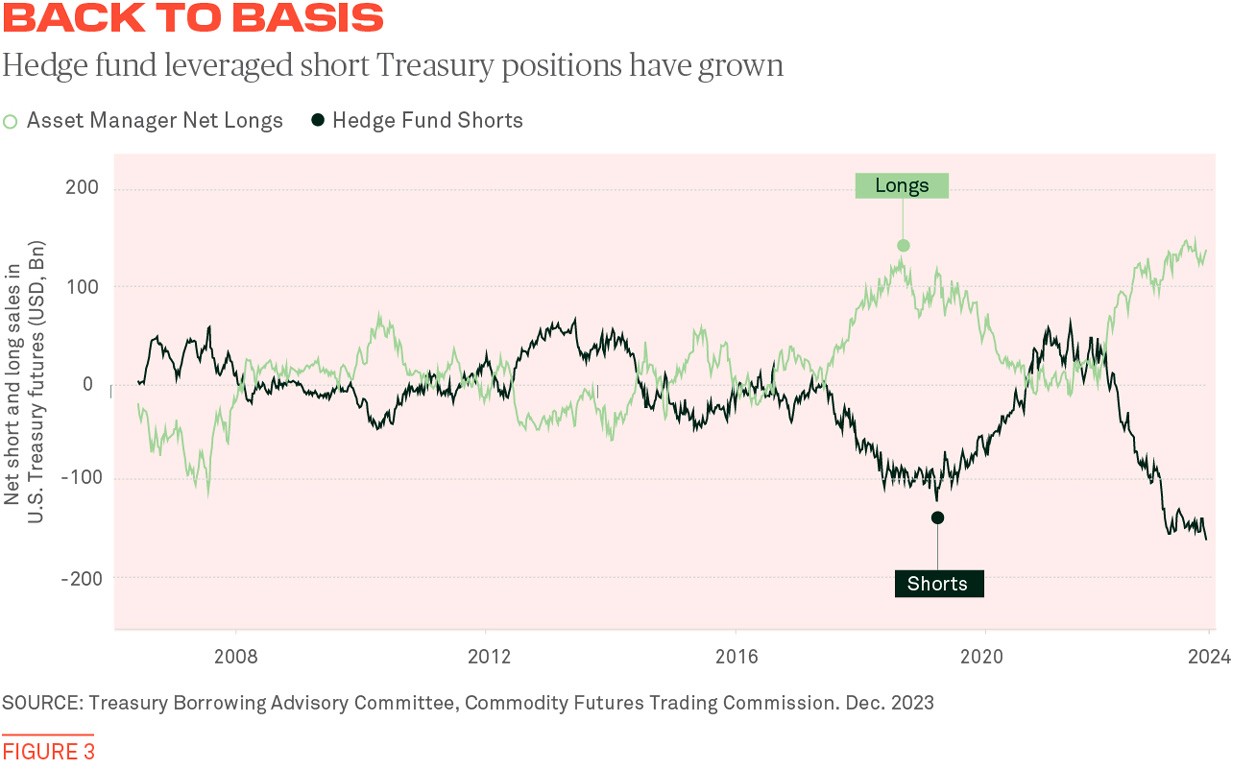

Add to that a buildup of leveraged trades in the Treasury market by hedge funds, and the potential has risen for financial instability to disrupt monetary policy.

“This is an incredibly sensitive time for the Fed,” explains Melissa Davies, chief economist at Redburn Atlantic, a London-based research firm. “It’s trying to orchestrate a soft landing, and the last thing the Fed wants is an event that forces it to flood the markets with liquidity before it’s reached its inflation target.”

Aerial View Bites

Melissa Davies of Redburn Atlantic on potential funding risks small and mid-size banks face today.

Red flags?

Lorie Logan, president of the Dallas Fed and former manager of the Fed’s bond portfolio, was the first to flag last year’s price spikes as the proverbial canary in the coal mine. These blips suggested “we’re no longer in a regime where liquidity is super abundant and always in excess supply for everyone,” she said in January while attending an industry panel on market monitoring.

The fact that the price spikes coincided with a sharp drop in excess liquidity, measured by the amount of cash that money market funds park at the Fed’s Overnight Reverse Repo facility (ON RRP), was identified as the issue. To Logan, it was an early signal that the Fed’s balance sheet reduction program could hit a stress point and that the central bank might need to slow it down to avoid a problem.

When the Fed is running off its balance sheet and not replacing bonds as they mature, the U.S. government needs to roll over that debt in the public Treasury market. That additional supply tends to push up yields on Treasury securities, including bills, luring short-term cash out of the Fed’s overnight reverse repo facility.

That was especially the case last year, when Treasury issuance reached levels not seen since the pandemic. And, while bank reserves have risen marginally over the past year, the increase has not been enough to offset declining usage in the Fed’s reverse repo tool.

Take-up of the Fed’s overnight reverse repos has fallen from $2.2 trillion last May to around $476 billion as of mid-March, at the same time as the Fed’s balance sheet has fallen by $1.4 trillion. The concern is that once excess liquidity in the Fed’s reverse repo facility is drained, purchases of newer Treasurys that will replace the ones the Fed is retiring will have to be funded with bank reserves because the market may not want to buy them.

The last thing the Fed wants is an event that forces it to flood the markets with liquidity before it’s reached its inflation target.

— Melissa Davies, Redburn Atlantic

Concentration risk

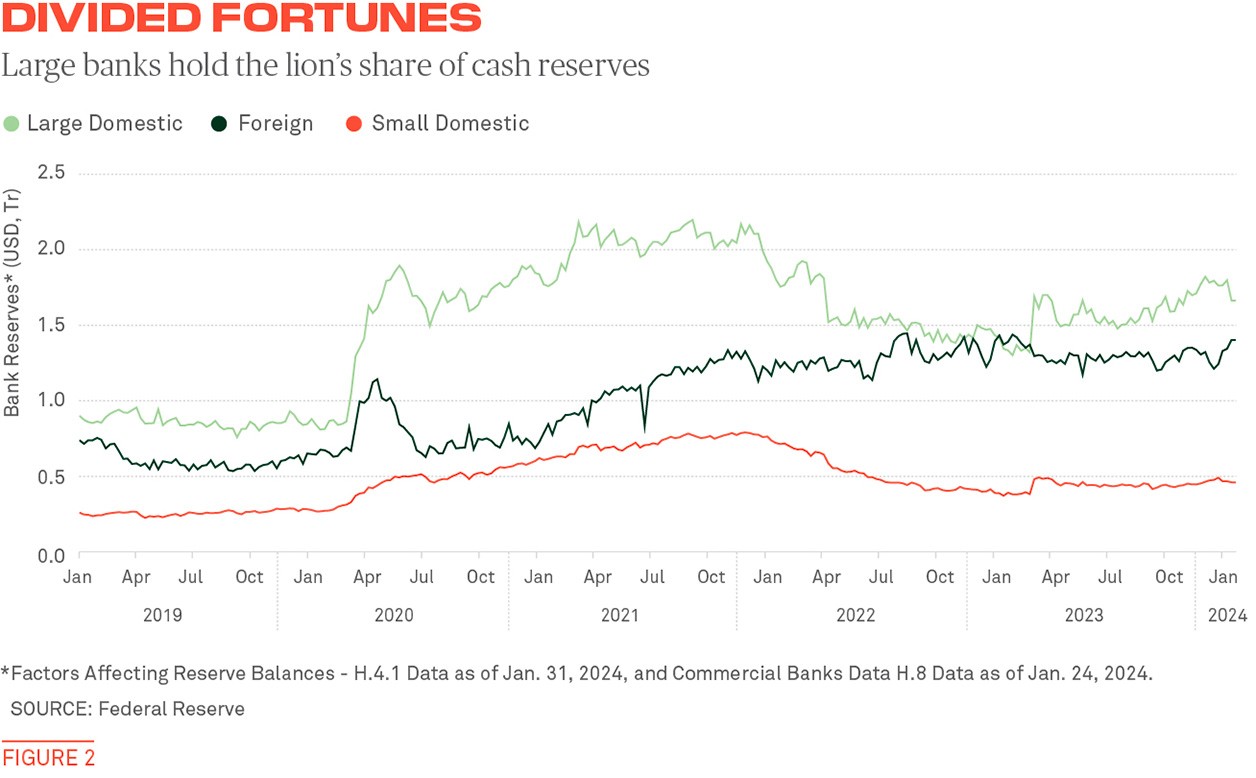

On the face of it, the U.S. financial system is awash with liquidity, with $3.5 trillion of bank reserves. That’s more than twice the $1.5 trillion that banks had at the Fed when the central bank finished its last balance-sheet tightening program. At that time in 2019, shrinkage in the bank’s portfolio caused a liquidity crunch that sent repo prices to intraday highs of 10%.

This time the worry is not so much a lack of reserves, but the fact that they may be unevenly distributed among the U.S.’s 4,000-plus commercial banks. As Logan said in her January speech: “Individual banks can [now] approach [reserve] scarcity before the system as a whole.”

Not only may reserves be unevenly distributed, but the majority of banks don’t want to part with them ahead of more regulations coming down the pike. The Fed’s most recent Senior Financial Officer Survey revealed that the 25 largest commercial banks have become increasingly wary of their reserves, with the majority wanting to maintain them at current levels.

While reserves at the largest banks have fallen a slight 13% since rate hikes began in March 2022, small domestic bank reserves have plunged more than 30% over the same period (see Figure 2).

“Concentration is at the core of the liquidity problem, and I don’t see any efforts to fix that,” said James Tabacchi, CEO of South Street Securities, a broker dealer in repos and Treasurys.

Some market participants say they are watching for potential funding strains on days when cash demand in the repo markets is typically high, like the March 31 quarter-end and tax day on April 15.

Scott Skyrm, executive vice president at broker-dealer Curvature Securities, is watching March 31 as a potentially challenging day, although he said the outcome is likely to be higher rates for repos and “more rate volatility rather than a blowup like 2019.” He also said he is expecting that balances in the Fed’s reverse repo facility could fall to zero by late April.

Aerial View Bites

Scott Skyrm of Curvature Securities on potential funding stresses in repo markets.

Regional planning

Concerns about small and mid-size bank balance sheets might prompt the Fed to slow down its tightening sooner than it had previously planned. John Velis, head of FX and macro strategy at BNY Mellon Markets, thinks that tapering the bond runoff will likely be implemented as early as June. “Some banks may be getting close to being short on reserves. It’s something that's clearly on the Fed’s mind,” he notes.

Slowing the pace of that program could help forestall liquidity strains in the broader repo market, but it’s not clear how much liquidity and capital smaller banks need to meet future regulatory requirements, cover nonperforming commercial real estate loans and manage their costs.

Concentration is at the core of the liquidity problem, and I don’t see any efforts to fix that.

— James Tabacchi, South Street Securities

On the asset side, some financial institutions reported lower net interest income in their fourth quarter earnings because of the cost of retaining customer deposits. Capital strains have also emerged. The New York Community Bank’s shares plunged after reporting a $185 million loss for the fourth quarter, after covering non-performing commercial real estate loans. The struggling lender has since raised $1 billion in capital and undergone a leadership shakeup.

Access to short-term funds outside of repo has also narrowed for the regional banks. Certain smaller banks have made use of the Fed’s emergency Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), which the central bank installed to deal with last March’s run on regional bank deposits. While the BTFP ceased making new loans on March 11, some banks took out one-year loans just before it expired. Smaller banks have also been discouraged from leaning on Federal Home Loan Banks for affordable short-term financing.

The Fed has indicated that banks should instead tap its discount window, but that could make matters worse by signaling weakness to the market, because banks use it only as a last resort. Regulators are seemingly trying to remove that stigma by making it mandatory for all banks to tap it once a year. The Standing Repo Facility is another tool the banks can use, and it can help set a ceiling on repo rates if volatility spikes. But banks also see a stigma attached to using it.

One bright spot is that federal securities regulators have introduced new rules for settling Treasury trades through central repositories called clearinghouses. Some participants are optimistic that expanded central clearing for Treasurys will improve liquidity over time, as new counterparties are expected to enter the market.

Another positive is the increased focus on liquidity management across Wall Street. Many borrowers have started to take out term repo loans, to lock in funding ahead of month-end and quarter-end, according to some repo broker dealers.

Aerial View Bites

James Tabacchi of South Street Securities on liquidity problems in the repo market.

Under pressure

It’s hard to imagine that the repo market will experience a repeat of its September 2019 liquidity crunch. Back then bank reserves were around 6.5% of GDP, compared to 12% today. Even so, Velis points to events on the horizon that could lead to “nontrivial shocks to the funding markets.”

The difficulty for central bankers is knowing exactly when to begin slowing down the balance sheet runoff. The Fed wants to target a point where reserves go from being as abundant as they are today, to being ample enough to keep the U.S. financial system running smoothly. That level has proven difficult to pinpoint in the past, and it may take repo price volatility to signal the crossover.

Some banks may be getting close to being short on reserves. It’s something that’s clearly on the Fed’s mind.

— John Velis, BNY Mellon Markets

“The risk here is that some banks will see reserves decline below their lowest comfortable levels before others,” says Velis. A broader risk, he says, is that bank reserves fall too far too fast, leading to funding stresses across money markets.

A liquidity event has the potential to increase other risks in the system, such as the impact of leveraged trades in the Treasury market. Some hedge funds arbitrage the pricing differences between Treasury bonds and the futures linked to them–the so-called “cash futures basis trade”–and those trades are funded in the repo markets. If overnight repo rates spike then “the economics of the trade don’t work and then you could see a disorderly unwind,” said Davies at Redburn Atlantic.

Aerial View Bites

Vincent Reinhart of Dreyfus and Mellon on the Federal Reserve's approach to regional banks.

According to a recent Bank of England report, citing Commodity Futures Trading Commission data, funds had about $800 billion of net short positions across Treasury futures in November of last year—one indicator of potentially outsized basis trading. Basis trades have since declined somewhat, in line with declining leveraged long positions by asset managers, now that rates appear to have peaked.

The Fed is trying to perfectly juggle a soft landing for the economy and balance sheet reduction. The last time it completed QT, in July 2019, there was a liquidity meltdown in repo markets, even though it thought bank reserves were at an ample level.

This time it is being even more cautious, and is expected to slow the pace of QT, before bank reserves are even close to being “ample.”

Danielle Robinson is a senior writer for Aerial View at BNY Mellon, based in New York.

Questions or comments?

Write to Nathaniel.Wuerffel@bnymellon.com or reach out to your usual relationship manager.