LEARNING TO LIVE WITH MORE TREASURY DEBT

The U.S. Treasury market is awash with supply at a time when some large buyers have pulled back. With no efforts in sight to curb government deficits, rising issuance could keep yields higher than markets expect, even after rate cuts.

Declining appetite among some traditional buyers of U.S. government debt is exacerbating investors’ concerns about surging new Treasury bond supply and the outlook for yields in 2024.

In less than a year the U.S. Treasury market has endured a debt-ceiling standoff, the loss of its triple-A rating at a second ratings agency,¹ ongoing threats of a government shutdown and relentless volatility as the Federal Reserve pushed rates to 20-year highs² to beat inflation.

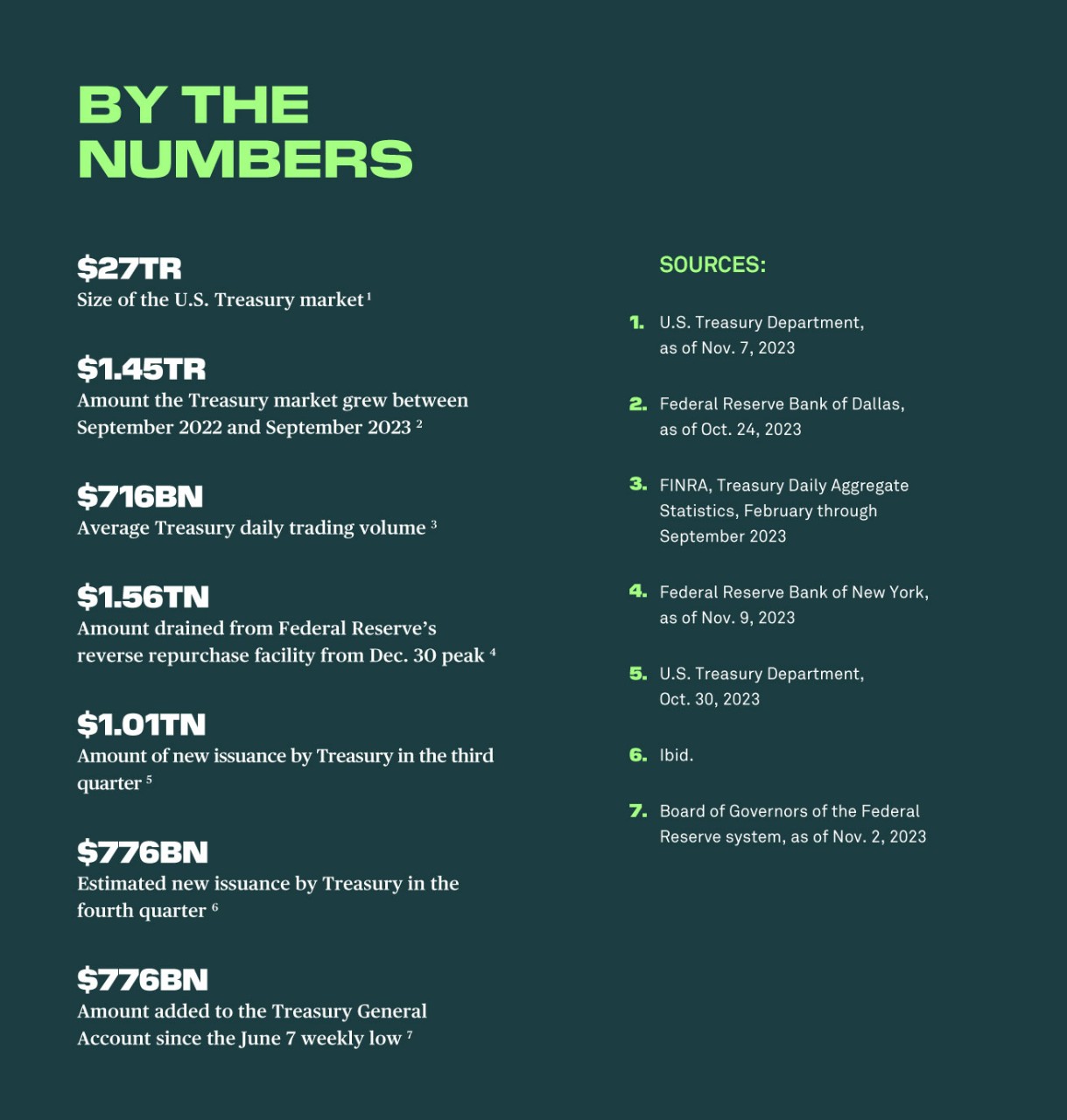

But the market’s biggest battle is only just beginning. Decades of federal tax cuts and increased spending during an era of historically low rates have left the U.S. government with $27 trillion³ of marketable Treasurys, much of which it will have to roll over at higher yields at a time when critical buyers have pulled back.⁴ It remains unclear when, or whether, those buyers will return in full force.

Treasury market debt is projected to increase by three quarters to around $47 trillion over the next decade,⁵ as precious tax receipts are eaten up by ever-increasing interest payments, higher Medicare costs and Social Security obligations associated with an aging population, as well as anticipated rising defense-related costs as geopolitical tensions worsen. And the government’s worsening debt profile has already started to bite.

Yields on the 10-year Treasury note hit their highest point since 2007⁶ in October, touching an intraday high of 5%⁷ from levels as low as 3.3% in April, after new bond supply in the third quarter reached its busiest quarterly pace since the height of the pandemic.⁸ Issuance is expected to reach another $1.6 trillion across this quarter and next.⁹

Monetary policy is typically the biggest driver of yields, and rising hopes that the Fed was finished with its rate hikes helped to push the 10-year yield down to just under 4.3% in November. But investor worries about fiscal policy are pushing up yields, too. As supply increases and demand wanes, investors are demanding more yield, called term premium, for new issuance in the near term, and for the risk that yields will continue to rise if the Treasury continues to issue more bonds (see Figure 1).

In past tightening cycles, the 10-year Treasury yield has typically fallen in the 12 months following peak federal funds rates and is likely to do so again. But the risk of ever-increasing supply could limit how far 10-year yields can rally this time around.

“Any decline in yields will be tempered by the higher-than-normal premium that investors will need as compensation if deficits keep rising,” says Scott Kimball, Chief Investment Officer at Loop Capital Asset Management.

Waning Treasury demand

The crux of the problem is not in the short end of the Treasury market, where there has been plenty of demand given that rates are at some of their highest levels in years. The issue is longer-dated maturities.

U.S. commercial banks and central banks, which have made up a huge share of total demand in recent years, have shown seemingly less appetite for Treasurys of late, having been scarred by mark-to-market losses on longer-term assets. Commercial banks’ holdings of Treasurys and government agency bonds have fallen by around $650 billion since February 2022, Fed data show. ¹⁰As a result of those losses as well as regulatory and supervisory pressures and shifts in depositor activity, some experts think that when commercial banks do return to these markets they will do so with an eye toward shorter-maturity debt.

The Federal Reserve, which engages in markets for monetary policy reasons rather than investing reasons, has also been reducing its holdings. As the Treasury Department tries to replace the central bank as a buyer, it will likely look to attract more price-sensitive investors like asset managers and pension funds into its longer-dated debt sales. Those private sector buyers will therefore be absorbing the risk of their bonds being hit by rising interest rates, but they will also be able to buy Treasurys at cheaper rates because the government will have to issue at higher yields to attract them.

The biggest hole in demand has been left by the Fed. Years of stimulus after the financial crisis and again during the pandemic made the Fed a regular Treasury bond buyer and left it with a peak of $5.8 trillion of Treasurys on its balance sheet by mid-2022. ¹¹Experts say it always intended to withdraw from the market once stability returned. It is now reducing the amount of Treasurys it holds as part of its quantitative tightening program (QT) and had taken its holdings down to $4.9 trillion by early November.

QT is a double-edged sword for the U.S. Treasury. Not only is the Fed no longer buying government debt, but Treasury also needs to issue more debt to the market to replace those that are rolling off the Fed’s balance sheet as they mature. The central bank would probably need to see some weakening of the U.S. economy between now and in the first few quarters of 2024 before it pivots to rate cuts and ends QT, Fed watchers say.

A persistently strong U.S. dollar has cut into the volume of official Treasury purchases from some international central banks like China’s, as greater dollar asset inflows weaken their own currencies. Non-U.S. investors including central banks and private financial investors held only 30% of outstanding Treasurys as of the second quarter, down from about 43% a decade ago, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. “Given that global central banks have been aggressively tightening policy, domestic rates have become more attractive,” explains Bret Barker, portfolio manager at TCW Group.

Given that global central banks have been aggressively tightening policy, domestic rates have become more attractive.

— Bret Barker, TCW Group

But many private-sector overseas buyers, including pensions, insurers and global asset managers, have been buying Treasurys because U.S. yields remain so attractive, daily data from BNY Mellon’s iFlow platform show. Since the end of August 2019 through the end of 2021, non-U.S. firms’ cumulative purchases of Treasurys fell around 50%, but since then have recovered by the same amount (see Figure 2).

Now that rates are higher around the world there are concerns, for instance, that Japanese investors, which have been some of the biggest foreign holders of Treasurys, may be lured back home if the Bank of Japan continues to encourage higher yields on Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs).

Meanwhile, U.S. domiciled real-money investors, or those investing their own or clients’ money, have been rushing in and out of longer-dated Treasurys as they apparently try to time a peak in yields. They were steady buyers of long-dated Treasurys in the summer, thinking that yields of around 4.5% were a good entry point. But iFlow data show that they capitulated in September as yields continued to rise and prices kept falling, leaving them catching a falling knife.

Some of these buyers once again re-entered the market in early November, following somewhat dovish Fed comments at the central bank’s latest rate-setting meeting and news that inflation cooled in October.¹² But market experts say they are now as price-sensitive as they have ever been.

Who will buy?

The Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee reported to the Secretary of the Treasury in late October that demand for Treasurys may have softened among several regular buyers, including commercial and foreign central banks.¹³ That was clear when a 30-year bond auction in early November was met with tepid demand.¹⁴

Treasury also surprised market participants with efforts to blunt the runup in yields by announcing it would issue far more Treasury bills, and fewer long-dated bonds, than expected in the coming months.¹⁵ It was a welcome sign that the government is willing to take market conditions into account and be more flexible with its usually consistent debt mix. But it can only massage the maturities of its issuance by so much. Like any large borrower, it needs to keep its debt liquid at all points on the curve (see Figure 3).

It also cannot take the demand for Treasury bills for granted. T-bills (maturing between one month and one year) have been bought in record amounts by retail investors choosing their 5%-plus returns over taking risks in other asset classes. This year, cash has also poured into money market funds, which are natural buyers of T-bills given their cash-like liquidity and safety. These funds had the added incentive to buy T-bills when those yields trumped overnight rates on their reverse repo (RRP) holdings at the Fed. The amount of money in the RRP program has plunged more than 60% year-to-date, falling below $1 trillion for the first time since August 2021,¹⁶ raising some concerns that this source of demand for short-dated Treasurys could subside.

“Once that facility is drained, it will be difficult for the Treasury to favor bill issuance over coupon issuance and it will thus need to term out its debt,” said Mike Sewell, a portfolio manager in T. Rowe Price’s fixed-income division.

To be sure, retail appetite for longer Treasurys could come from some of the roughly $6 trillion¹⁷ of cash sitting in money market mutual funds. But experts say retail is not a large enough portion of the market to make a meaningful difference beyond marginal buying and current interest is focused on the short end.

Once [the Fed’s reverse repo] facility is drained, it will be difficult for the Treasury to favor bill issuance over coupon issuance and it will thus need to term out its debt.

— Mike Sewell, T. Rowe Price

Market participants expect the Fed to end its QT program when it eventually pivots to rate cuts, with consensus expecting that to happen around mid-2024. But that doesn’t mean the Fed is going back into the business of buying Treasurys any time soon, or at least not at the same pace and length of time as it did when it began its Quantitative Easing (QE) program after the 2007-2009 global financial collapse.

“I think the Fed will resume quantitative easing if and only if long-dated Treasurys do not rally during a recession,” Sewell said. “This would likely occur if the market believed that fiscal deficits will expand.”

Term premium tantrum

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said in October¹⁸ that the extraordinary rise in long-term Treasury yields in that month was not because of the rise in Treasury issuance, but a reflection of the Fed keeping rates higher for longer.

Some indicators suggest otherwise. Issuance of two-year and longer Treasurys rose nearly 10% from mid-July to mid-October while the term premium—the extra yield that compensates investors for risks other than rate moves—rose from minus 95 basis points to a positive 47 basis points.¹⁹

“This correlation shows a clear connection between rising supply and rising yields, and we think that trend will continue,” according to John Velis, BNY Mellon’s FX and macro strategist for the Americas. “It means that even if rates are cut, this term premium portion of the 10-year yield will still be present, keeping rates higher than they would be if the yield only reflected future expectations for inflation.” He expects the 10-year yield to reach 5.25% or more next year.

One way to tackle the problem is for the U.S. to grow its way out of its increasing debt burden. But the Congressional Budget Office projected on September 8 this year that gross federal debt (Treasurys outstanding and federal agency debt) will amount to 124% of gross domestic product (GDP) at the end of fiscal year 2023 and 192% by 2053.²⁰

We interpret rising yields as a sign that the bond market is at the early stages of warning Washington on fiscal policy.

— Dan Clifton, Strategas Securities

The focus on Congress’s inaction is intensifying. Fitch Ratings downgraded the U.S. earlier this year because of concerns around Congress’s inability to improve the government’s fiscal path, and the U.S. may lose its last remaining triple-A rating, from Moody’s Investors Service if Congress fails to pass the current budget. Moody’s put the U.S. on credit watch negative November 10, pointing to risks to fiscal strength and political polarization in Congress.²¹ The House and Senate in mid-November approved a plan to extend part of the government’s funding through January 19 and another part through February 2.²²

One of the biggest concerns for many bond investors is how quickly the government’s interest expense will rise as a percentage of total deficits (see Figure 4). For 15 years, low inflation and low interest rates enabled the U.S. government to increase spending and cut taxes without much impact to debt servicing costs. But those days are gone and aren’t likely to return if inflationary pressures persist and investors keep pricing in compensation for rising supply.

The higher the government’s interest expense goes, the greater the risk of a negative feedback loop, where the federal government is faced with high interest expenses adding to its deficit, and then a need to increase Treasury issuance, which increases interest expenses again, and so on.

This is the kind of dynamic that can lead to investors demanding even higher yields, meaning the Treasury will need to steepen what it pays on longer debt in particular. Dan Clifton, partner and head of policy research at Strategas Securities, is concerned that the recent selloff shows investors are already at that point.

“We interpret rising yields as a sign that the bond market is at the early stages of warning Washington on fiscal policy,” he said. “The period of low rates was an incredible era in U.S. fiscal policy and investors are waking up to the reality that it’s now over.”

Danielle Robinson and Jon Vuocolo are senior writers for Aerial View at BNY Mellon, based in New York.

Questions or comments?

Write to John. Velis@bnymellon.com or reach out to your usual relationship manager.

- https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/fitch-downgrades-united-states-long-term-ratings-to-aa-from-aaa-outlook-stable-01-08-2023

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/fedfunds

- https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/datasets/debt-to-the-penny/debt-to-the-penny

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USGSEC

- https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59159

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS10

- https://www.wsj.com/finance/investing/bond-rout-drives-10-year-treasury-yield-to-5-ab74c98e

- https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm997

- https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1851

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USGSEC

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=tRur

- https://www.wsj.com/livecoverage/stock-market-today-cpi-report-inflation-11-14-2023/card/october-cpi-report-here-s-what-to-expect-IoD4SMHAyAOnySxsq7lM

- https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1865

- https://www.wsj.com/livecoverage/stock-market-today-dow-jones-11-09-2023/card/demand-for-30-year-treasurys-proves-weak-sending-yields-surging-oIJ5kBDb2sytqyspLC6x

- https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1851

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RRPONTSYD/

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MMMFFAQ027S

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-10-26/yellen-says-increase-in-yields-reflects-higher-for-longer-rates

- https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/data_indicators/term-premia-tabs#/interactive

- https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59512

- https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-changes-outlook-on-United-States-ratings-to-negative-affirms-Rating-Action--PR_480815

- https://www.wsj.com/politics/policy/both-parties-lose-appetite-for-government-shutdown-standoffsfor-now-c67015d9?mod=politics_feat1_policy_pos2