An Uncertain Future for Prime Funds

Mapping the Road Ahead for Prime Funds

An Uncertain Future for Prime Funds

Mapping the Road Ahead for Prime Funds

June 2020

By Peter Madigan

Investors fled institutional prime funds en masse in March, forcing the Federal Reserve to shore up the sector for the second time in 12 years. Following the weaknesses exposed during the recent episode, some argue it is time to re-evaluate the future of these vehicles.

Financial crises have had a tendency to dent appetites for certain investment products, or even kill them off altogether. The 2008 crash famously drove parts of the securitization market, emblematic of the wretched excesses of the U.S. mortgage bubble in the mid-2000s, into near extinction.

Which financial products may ultimately be counted among the casualties of the COVID-19 crisis is far from clear. Several investment vehicles suffered extreme stress at the hands of the pandemic-induced melt down this past March — although they have not disappeared. One of those was the institutional prime fund.

Unlike government money market funds, which restrict their holdings to U.S. Treasuries and agency debt, prime money market funds also hold other assets, such as short-term corporate debt like commercial paper (CP), and bank-issued certificates of deposit (CDs).

Holding short-term corporate debt typically allows prime funds to pay investors a higher yield, often around 25-30 basis points (bps) more than a government-only fund. The trade-off for that yield enhancement is reduced liquidity during times of stress, because the holdings are not backed by the government and are often issued for 60 days, 90 days or longer.

Although there is a healthy secondary market for CP, during a panic like the one set off by COVID-19, liquidity in the CP market can evaporate. This is precisely what happened in March as investors bolted out of prime funds.

As governments introduced sweeping stay-at-home orders to limit the spread of COVID-19 that month, financial markets turned volatile as the extent of the shock from an unprecedented economic shutdown became apparent.

A global scramble for liquidity ensued, as corporates, governments, banks and asset managers sought to stockpile cash. Many turned first to cash equivalents like money market funds, because withdrawals tend to be quick and easy, but a clear delineation in liquidity was evident between the different institutional prime and government money market vehicles.

"We heard from clients that they were drawing down cash reserves from prime funds to make payroll and other short-term cash needs."

— Deborah Cunningham, Federated Hermes

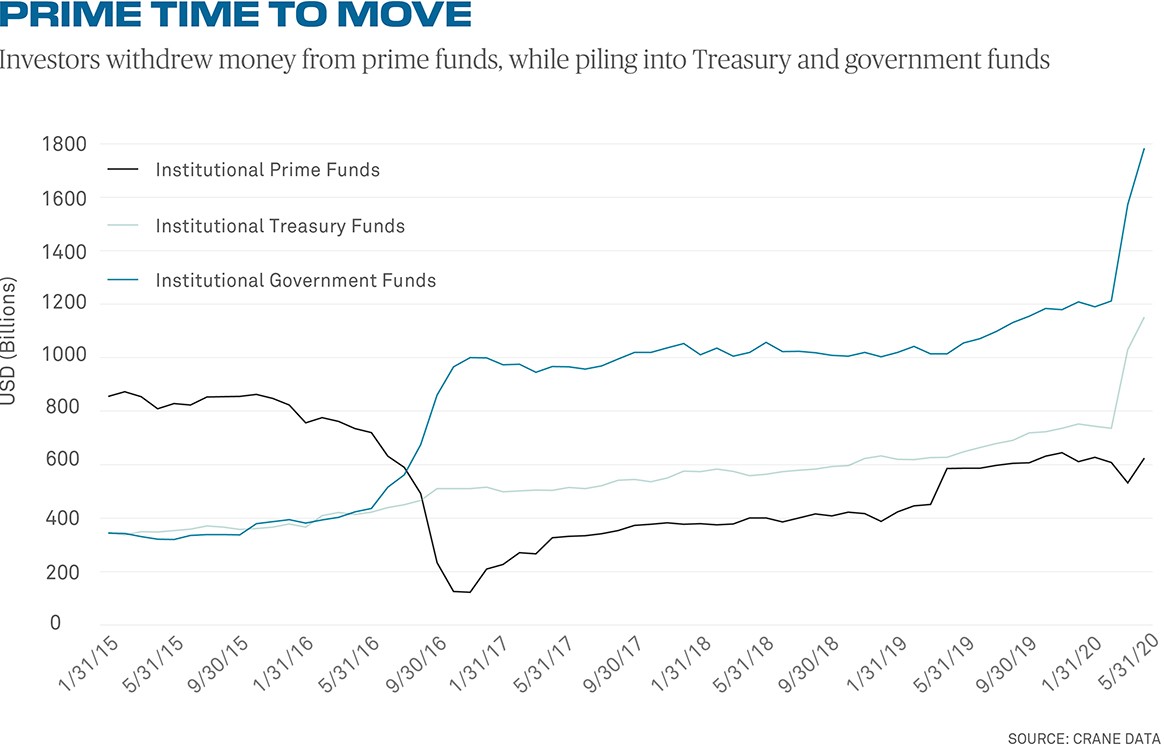

Between January 31 and March 31, investors withdrew $95 billion from U.S. institutional prime funds, approximately 15% of their total fund assets, according to Crane Data. The story was very different in the other classes of institutional money funds. Over the same period, Treasury funds saw their balances increase by $287 billion and government fund balances grew by $383 billion.

“The rush to cash was the main driver behind these flows,” says Deborah Cunningham, chief investment officer for global liquidity markets at Federated Hermes. “We heard from clients that they were drawing down cash reserves from prime funds to make payroll and other shortterm cash needs.” Any additional cash that they were receiving they were putting into government funds, she added.

Gates and Fees

While investors were frantically trying to raise cash in mid-March, the disparity between different money market fund types demonstrates that market participants had very specific reservations about the liquidity in prime funds.

There are two plausible explanations for this. The first is that as liquidity dried up in CP markets, investors bolted from prime funds out of fear that mounting illiquidity in short-term corporate credit would prevent them from being able to withdraw their funds at a moment’s notice.

As investor redemptions flooded in, prime funds turned to their dealer counterparties to take CP off their hands in order to meet the requests. This abrupt surge in funds simultaneously attempting to offload CP overwhelmed dealer balance sheet capacity, forcing dealers to temporarily step back from intermediating in the secondary market. As a result, liquidity all but evaporated in CP markets during the week of March 16.

A second explanation as to why investors pulled cash out of prime funds, but not other money funds, centers on the regulations implemented in the market in 2016. Importantly, these changes did not affect institutional government funds or retail money market funds.

In October of that year, new Securities and Exchange Commission rules took effect that were designed to bring more transparency into institutional prime funds by imposing a floating net asset value (NAV) instead of a $1 fixed price per share. The change was designed to enable investors to know at all times the exact value of their position.

In addition, to address the risk of runs on an institutional prime fund, the SEC allowed fund boards to impose a 2% redemption fee and temporarily halt redemption requests by imposing “gates” preventing assets from being withdrawn if the weekly liquid assets of the fund fall below 30% of its total assets. This change was aimed at ensuring funds keep enough of a liquidity buffer to counter sudden, large investor withdrawals.

It was the possibility of breaking that 30% threshold—and a fund board considering imposing a redemption fee or a gate if that were to happen—which prompted two fund sponsors to step in and buy assets from their prime fund affiliates that week.

No board of directors is known to have imposed either fees or redemption gates during the height of the March market dislocation, but many observers are strident in their opinion that the 2016 regulations only height ened investor outflows at the time, instead of alleviating them.

“The 30% weekly liquidity threshold for gates and fees was essentially pulled out of thin air by the regulators — there was no quantitative modeling conducted, which said that 30% is the optimal number,” says James Angel, associate professor in the McDonough School of Business at Georgetown University.

Another issue is that 10% of prime fund assets have to mature overnight to meet daily liquidity requirements, in addition to the 30% that has to meet weekly liquidity requirements. According to Professor Angel, if funds fear they will face more redemptions than their maturing paper will accommodate, they will sell their most liquid assets first, leaving the less desirable assets for the investors remaining in the fund.

"If six months from now the Fed and the SEC announce they are going to reexamine money market fund regulation, I would not be surprised."

— Jonathan Spirgel, BNY Mellon Markets

During the SEC comment period, when the 2016 rules were out for public consultation, many industry letters warned that, far from preventing investor outflows, the looming specter of redemption gates would actually heighten the risk of runs as investors rush to withdraw their cash before gates are imposed. Given the outflows from institutional prime funds in March, some of those commentators feel at least partially vindicated.

“A lot of people would argue that the reason there was a run on institutional prime funds is because of the implementation of fees and gates. If there had been no fear of fees and gates, would the run have happened? I think that’s an unanswerable question,” says Jeff Glenzer, chief operating officer of the Association for Financial Professionals.

The Path Ahead

The fact that the Federal Reserve had to launch not one, but two, facilities to restore order in short-term debt markets has been taken by some as evidence that the prime fund sector retains long-standing structural weaknesses that make it uniquely vulnerable to market shocks.

The new Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility allows intermediaries like broker dealers to borrow money from the Fed and use the cash to buy collateral for the loan from money market funds in the form of CP, CDs, U.S. Treasuries and other assets. This enabled prime funds to sell their assets at reasonable prices when the market was frozen, giving them an outlet to raise liquidity. In concert with the Commercial Paper Funding Facility, which positioned the Fed as the buyer of last resort for CP directly from issuers, the U.S. central bank managed to successfully unclog the short-term debt markets and liquidity stresses began to ease by early April.

Flows into institutional prime funds subsequently began to increase, surging $91 billion from the March 31 low to $623 billion by April 30.

Yet, ominous signs remain. On May 14, Northern Trust decided to close its $1.7 billion Northern Institutional Prime Obligations Portfolio and will be liquidating its assets by July 10, the company said. Additionally, many believe that in light of the COVID-19 dis location, regulators may opt to revisit the issue of prime fund regulation.

"A lot of people would argue that the reason there was a run on institutional prime funds is because of the implementation of fees and gates."

— Jeff Glenzer, Association for Financial Professionals

“If six months from now the Fed and the SEC announce they are going to reexamine money market fund regulation, I would not be surprised,” says Jonathan Spirgel, global head of liquidity and segregation services at BNY Mellon Markets. “Although much of that renewed attention will likely be around redemption fees and gates, the transition from a fixed to a floating NAV appeared to work as intended in boosting confidence during the stress period.”

The flip side is that increased liquidity may come at the price of a reduced yield. Advocates have argued that the future of prime funds is assured by the crucial role they play in the CP market and the invaluable short-term liquidity they provide to corporate America.

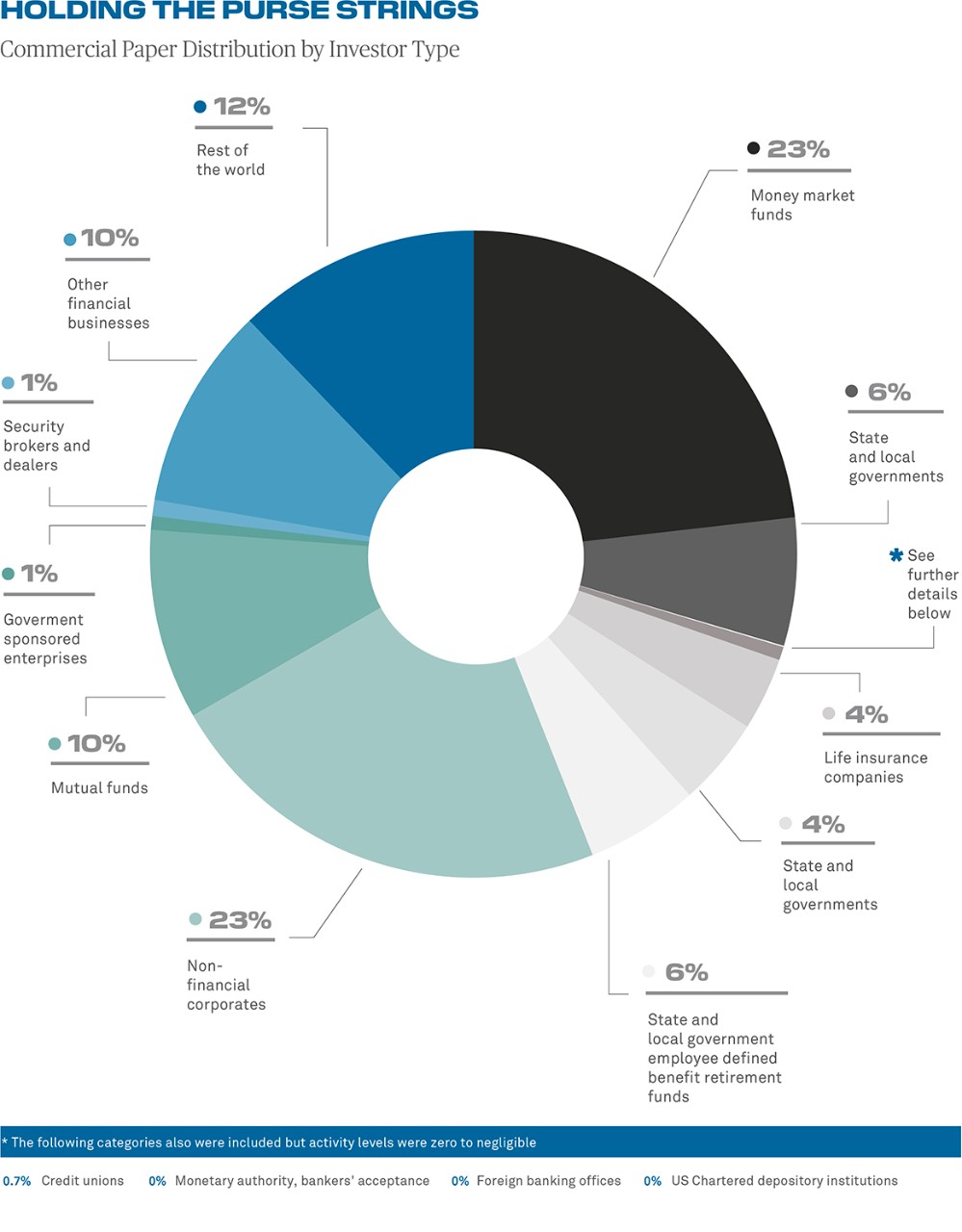

Between the two of them, 2a-7 funds and separately managed accounts (prime funds fall into both categories) represent around 40% of buyers, making money funds by far the largest investor type and emphasizing the important role they play in funding.

Nevertheless, until recently prime funds were significantly larger buyers of CP. In 2015, the year before the U.S. money market regulations took effect, prime fund balances were as high as $872 billion, according to Crane Data. Balances dropped precipitously as the late 2016 deadline for the new reforms approached, bottoming out at just $125 billion on October 31 that year.

Although prime fund balances today are north of $620 billion, the historical data illustrate that the CP market has absorbed an almost nine-fold reduction in prime fund buying capacity, and corporate issuers were still able to secure short-term financing without much difficulty. This suggests that a dramatic reduction in the number of U.S. prime funds in the market may not be all that disruptive to issuers.

Other proposed structural changes to prime funds include the imposition of capital buffers provided by fund sponsors that would absorb redemptions and circumvent the issue of attempting to liquidate CP in a downturn.

Amid the uncertainty, one thing that seems likely is that once the current crisis is behind us, prime funds will again come under regulatory scrutiny. It remains to be seen whether any future changes would rescind fees and gates or impose maturity lim itations in their holdings.

“Money funds make almost no money; their margins are razor thin,” says Drew Winters, professor of finance in the Rawls School of Business at Texas Tech University. “If they want to fix this sector, they should start by rolling back the 2016 reforms.”

Peter Madigan is editor-at-large for BNY Mellon Markets.

Questions or Comments?

Contact Kenneth.McDonnell@bnymellon.com or reach out to your usual BNY Mellon relationship manager.