An Existential Threat to the US Dollar

Is the dollar’s position as the world’s preeminent currency set to be challenged?

An Existential Threat to the US Dollar

Is the dollar’s position as the world’s preeminent currency set to be challenged?

September 2020

By Daniel Tenengauzer, John Velis and Geoff Yu

A new spirit of fiscal union in Europe and China’s ambitions for a larger role for the renminbi in global commerce may call into question the US dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency.

Over the past 20 years, academics, policymakers and market participants have begun to debate the future of the US dollar (USD) as the world’s premier reserve currency, or the currency in which global central banks prefer to hold their foreign exchange reserves. Some of them have concluded that the USD’s prized status could be in jeopardy.

The discussion started in 2005, when Barry Eichengreen, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote a paper opining that the status of the USD as a reserve currency would not be challenged by the Chinese yuan within 20 or even 40 years, but that the USD may increasingly come to share its preeminent position with the euro.

In 2010, the US Treasury Department published a note in which it argued that economists tend to cite six key factors determining the use of a currency for reserves: GDP, exports, domestic capital markets, convertibility, currency regime and macro policies.

The US dollar still scores the highest in at least five of these, but the creation of the eurozone and China’s entry into the World Trade Organization heralded the beginning of an era in which the USD’s reserve status may no longer be taken for granted. For one, US foreign policy activism and eurozone foreign policy absenteeism, along with the bloc’s embrace of sustainable policies, could push for higher euro allocations.

Meanwhile, China’s innovations in financial markets, particularly in payments and blockchain, will continue to attract flows into yuan-denominated instruments. China’s reserve managers are also realizing that staying overweight US Treasuries is not only an inefficient allocation of reserve assets but also a financial stability risk susceptible to the whims of geopolitics.

Challenging the Established Order

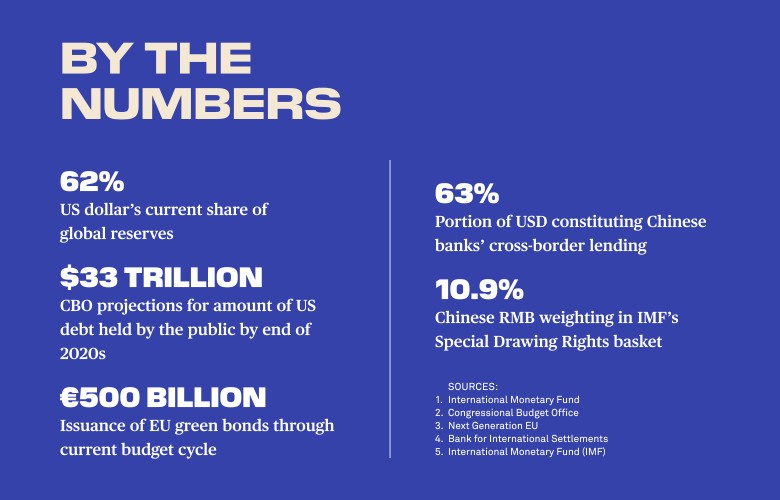

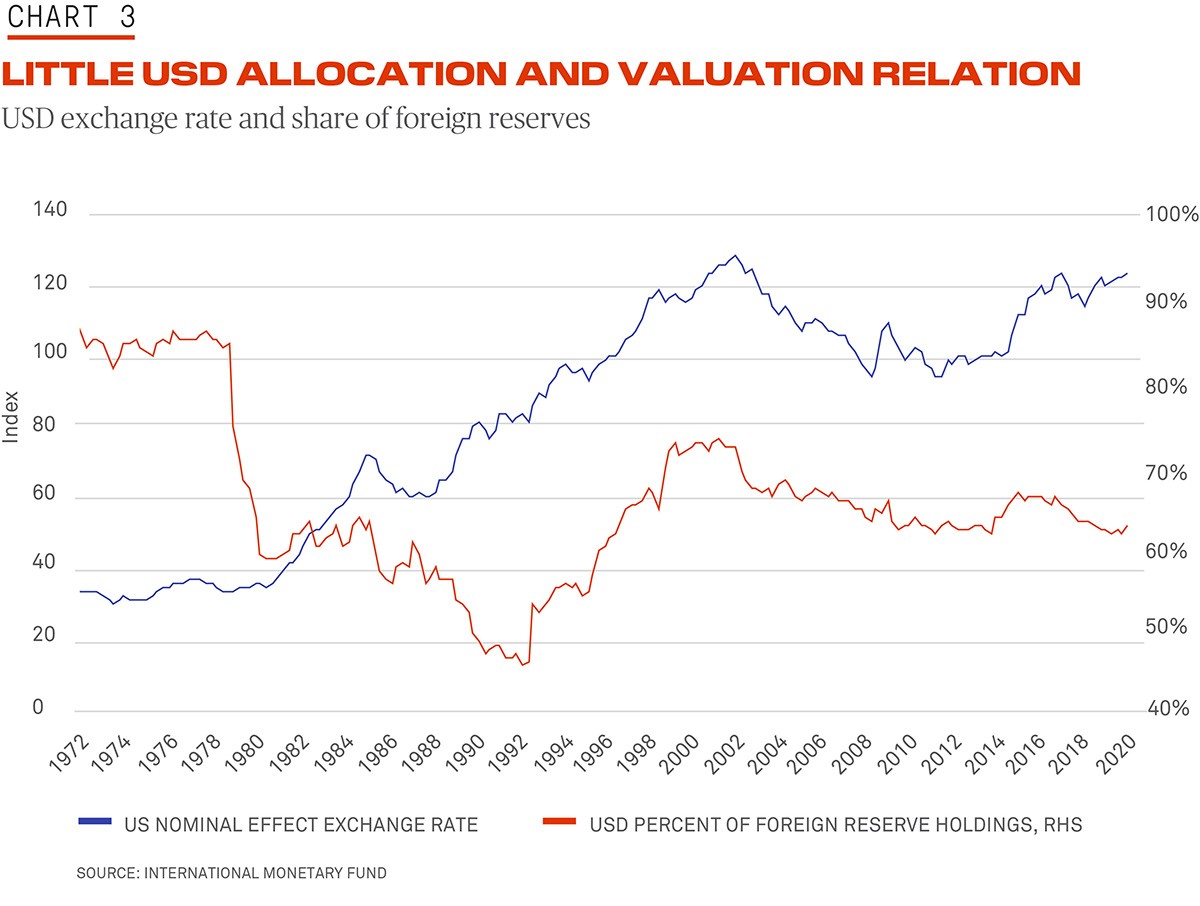

Today the USD remains the world’s premier reserve currency. The most recent data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) show that the USD accounts for just under 62% of global currency reserves. Over the past two decades this proportion has fluctuated between 72% and 60%.

Beyond its role as the world’s dominant reserve currency, the USD’s preeminence in global trade and financial markets has persisted since at least the end of World War II, with some monetary historians dating its ascendancy back to the beginning of the 20th century. Twenty years into the 21st century, however, is the USD’s primacy secure?

Consider the lofty perch the USD occupies in the global monetary hierarchy. In addition to being the largest reserve currency, it is the currency in which most global trade is invoiced and the currency with the greatest weighting and turnover in international financial markets. It is also the most transacted currency in global foreign exchange markets. This dominance and its international use cements the USD’s current position as the world’s de facto reserve currency, as Chart 1 illustrates.

Perhaps the foremost prerequisite for a successful reserve currency is that the issuer nation needs to be a large economy. It also requires deep, liquid and open capital markets, a relatively stable valuation and policy credibility.

The status of the USD allows the US, as its issuer, to run large international deficits in its own currency, and has allowed international liabilities to be paid off at a lower rate of interest than the US receives in income from abroad.

One of the prices that the US pays for this privilege is the Federal Reserve’s de facto position as the world’s central bank. In 1971, as the era of fixed exchange rates was coming to an end and with the US — and other major economies — gripped by high inflation, US Treasury Secretary John Connally famously quipped to his French counterpart that the USD was “our currency, but your problem.” This illustrates how crucial credibility is to sustaining the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

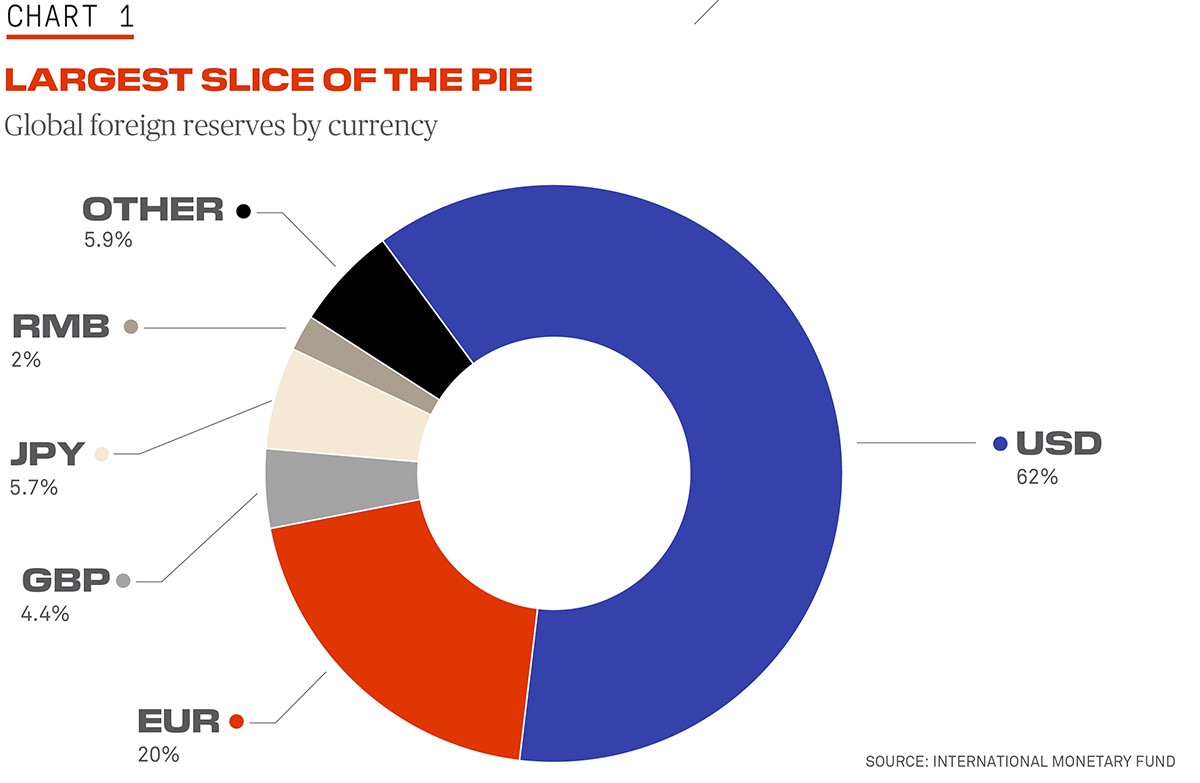

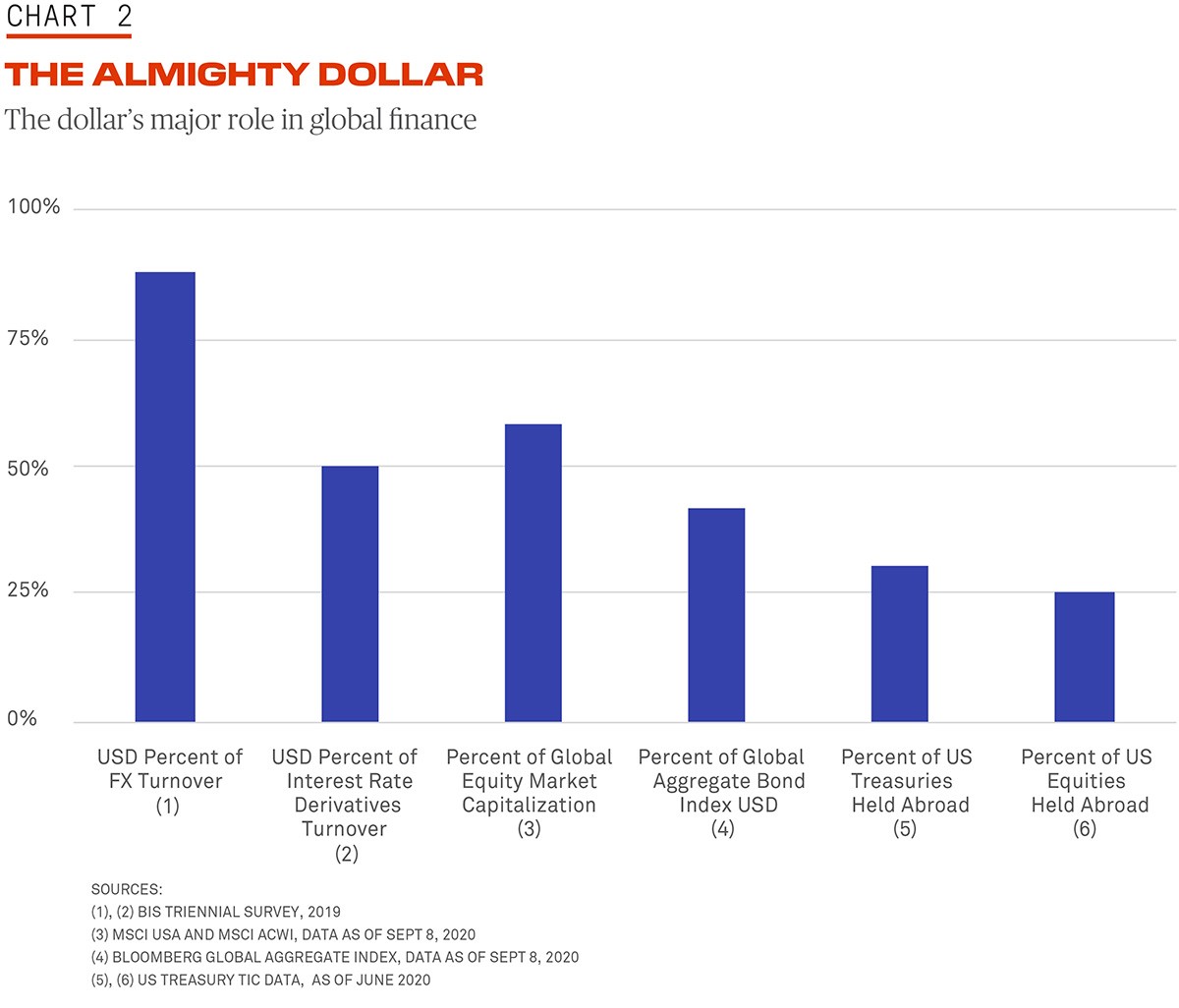

Dollar weakness or strength, per se, doesn’t threaten its position as the global reserve currency, as Chart 2 demonstrates. The USD’s appreciation during the 1990s certainly corresponded to an accumulation of dollar reserves, as did its depreciation during the 2000s. But the USD’s recent fall in itself does not presage an imminent major realignment of global reserve currencies.

The USD’s status as the world’s reserve currency is not etched in stone, however, and the COVID-19 pandemic could herald the start of a process that marks the fall of USD from its preeminent position.

According to the latest report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the 2020 US federal budget deficit is projected to be $3.3 trillion, or 16% of GDP, a post-war record. By the end of the decade, the CBO projects US debt held by the public to exceed $33 trillion, more than 108% of GDP. Issuing so much new public debt, and the Fed’s roll in absorbing that issuance, undermines the attractiveness of the USD, especially if inflation erodes the value of the currency significantly and threatens the credibility of the Fed itself. Steps to limit trade and financial flows internationally would also reduce the dominance of the USD.

Of course, for the dollar to lose its status as the global reserve currency, there need to be alternatives. In this light, the yuan and the euro could be considered candidates to attract a larger share of reserves — the former especially as Chinese financial markets develop and become more open.

The Euro and ESG

The euro’s relative attractiveness is growing as a result of the EU’s environmentally friendly and socially conscious approach.

While the focus of the bloc as a whole has been on mutualizing fiscal resources, the timing of negotiations around the eurozone recovery fund, under the Next Generation EU project (NGEU), also allowed the upcoming EU budget to become a “green” one to satisfy the European Green Deal (zero net emissions by 2050), while the COVID-19 pandemic presented an opportunity for EU governments to accelerate the processes. It is also easy to foresee the EU becoming the biggest issuer of green bonds in financial markets — over $500 billion through the budget cycle and at least $150 billion over the next two years, according to NGEU’s financing and expenditure targets. It should be simple to reclassify comparable NGEU debt instruments as green or environmental, social and governance (ESG) bonds.

This is a new asset class where private- and public-sector demand will likely be high; the European Central Bank has even pledged to look into including these bonds into its asset purchase programs. Reserve managers would similarly express strong interest in national level green bonds. Germany has established a “twinning” framework, whereby green bonds can be swapped with conventional bonds with fully matched parameters. France issued its first “Green OAT” in 2017 and will produce internal and external “allocation and impact reports” to verify that expenditures have matched the stated intentions when issued.

We believe these green initiatives will make an enormous difference to euro preferences by the official sector. Although ESG-based investing has been led by the private sector, reserve managers and sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are moving in the same direction. Perhaps due to their own individual legacies, petrodollar SWFs are taking the lead in this area and continue to seek a combination of direct investment and conventional asset classes to allocate funds.

The euro’s relative attractiveness is growing thanks to its environmentally friendly and socially conscious approach.

The IMF estimated in 2019 that interest in sustainable investing rose to close to $900 billion. Although the bulk of the interest remains in equities, 15% of the asset allocation went into fixed income. It is reasonable to assume that public sector investments could move up to, or beyond, a similar weighting in their new asset allocation frameworks over time. A recent study on SWF investment trends showed that for equity investments, these funds take the ESG performance of target firms into account in their equity investment decisions. Similar principles would apply to fixed-income and country-level investments.

Under the direction of the EU and national governments, we expect EU companies to strengthen their positioning in ESG. This will be attractive to SWF asset allocation and strengthen demand for euro liquidity as the EU’s policies align with sovereign investors’ investment objectives.

Renminbi as a Reserve Asset

Since the beginning of the last decade, renminbi (RMB) internationalization has been a strategic goal for Beijing. Efforts culminated in RMB’s inclusion in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket of currencies in 2015, but since the devaluation that year (Beijing preferred to call it a “valuation adjustment”), it has taken time for markets to reestablish confidence in the currency. The trade war with the US, structurally lower growth rates, and comparatively shallow capital markets in China continue to hinder the RMB’s development as an international currency.

China has also never been exactly clear in how it wanted to internationalize the currency. In fairness, there is no tried and tested approach in modern times. The emergence of USD supremacy was the result of a unique confluence of events and there is no expectation that the RMB would copy that playbook.

The experience of China’s 2013-2015 drive for internationalization showed that once yields, growth trajectory and investment returns are no longer aligned, private- and public-sector demand can fall away quite easily, underpinning the USD.

The financial aspects of the Sino-US trade war in recent years, in which Chinese exposure to the USD’s structural advantages was made abundantly clear, has also focused minds in Beijing. Beijing realizes that impediments to Chinese firms’ access to USD financing and payments could grow materially, so participating in alternative systems has moved up the agenda.

USD supremacy was achieved through the US providing financial resources to generate external demand for US goods and services, and now China is attempting the same, either through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) or through the initiative of enterprises, targeting not just emerging markets but other economies open to a hearing of such plans.

In practice, the BRI has had its ups and downs. The circumstances are radically different compared to the post-war rebuilding of Europe, and the BRI itself has faced political difficulties on a local and international level.

Nonetheless, the biggest problem is that organic demand generation is difficult: counterparties who are able to choose which currency to transact in remain incentivized to revert to a ready-made USD system for the sake of convenience and accessibility. It has been well documented that firms receiving RMB financing will swap funds for USD thereafter — to the extent that Chinese banks remain active lenders of USD.

According to data from the Bank for International Settlements, the dollar continues to constitute 62.72% of total cross-border lending by Chinese banks, as of Q1 2020.

As the share of EUR and JPY lending is very small by comparison (less than 7%), we can assume the remaining 30% of cross-border loans are RMB-denominated. The USD number looks impressive but in reality the share is below the 2016 high of 65.2%.

If we adjust for intra-banking group transfers, which are unlikely to be used to finance “real” demand or investment, and are likely just a function of moving US dollars from one jurisdiction to another, the share of USD lending falls to 48.9%, up from 45% in Q1 2018.

In absolute terms, US dollar cross-border lending to banks (excluding loans between branches or subsidiaries of the same banking group), non-bank financial institutions and non-financial institutions hit a record $1.56 trillion in Q1 2020 — a jump of over $200 billion since the beginning of 2018.

It seems that the response to the trade war and politicization of the USD during the same period did not propagate a pickup in the efforts of Chinese financial institutions to popularize the renminbi. In a market as efficient as cross-border financing, it is quite indicative of weak demand.

Yet, demand is slowly picking up and China is happy to take baby steps amid a more favorable geopolitical environment where there is genuine demand for greater choice in reserve assets, cross-border lending and payments. China has sufficient scale and potential to offer such a choice.

Similar to the story of RMB internationalization, take-up of the RMB as a reserve asset has been slow. Lack of deliverability is just one of the many major barriers to faster growth. However, in absolute terms holdings have risen in 12 out of 13 quarters for which the IMF has data. The share in allocated reserves has also almost doubled since the end of 2016. A simple realization of the RMB’s weighting in the IMF’s SDR basket (to 10.92%) would require an additional $800 billion of purchases of RMB-denominated assets by the world’s reserve managers (excluding China).

Beijing’s ambitions are to use technology to bypass the current dollar-based international financial system altogether.

The RMB’s share in the SDR basket will likely rise further in the upcoming quinquennial review, and China is widening external accessibility and increasing the breadth of investable assets to meet the anticipated rise in inflows.

This year’s Chinese Government Bond (CGB) issuance, at very favorable yields (hedged and unhedged), has already surpassed 2019 levels. Part of this is attributable to the pandemic response, but the global demand is also there to support the market; our iFlow data show heavy purchases of CGBs in our custodial flows.

Finally, China is not only challenging the USD system through the renminbi, but also through shaping the future of money itself.

Through digitization of the entire monetary base and a speedy payments framework, Beijing’s ambition is to use technology to bypass the current USD-based international financial system altogether.

A Multi-Polar Future

As Henry Kissinger mentioned in a discussion at the Wilson Center two years ago, “We’re in a position in which the peace and prosperity of the world depend on whether China and the United States can find a method to work together, not always in agreement, but to handle our disagreements. But also, to develop goals which bring us closer together and enable the world to find a structure.”

The status of any global currency will have to accommodate this delicate balance. Enter the euro, a liquid and reasonably neutral alternative, where an emerging common fiscal policy and a new ESG push may act as a buffer and a formidable alternative to the USD.

The battle for winning a reserve currency spot is not necessarily about solid macro fundamentals. The micro is more important because the user must withstand two simple tests. First, the hurdles to buy or sell the currency today. Second, the hurdles to buy or sell the currency tomorrow. The USD remains the dominant, easiest currency to transact today, justifying reserve managers’ current 60% allocation.

A changing global order implies that this unique position started being challenged 20 years ago. As a result, we expect heightened uncertainty with respect to the second question going forward. Even assuming eurozone economic sanctions follow the US, the risk of additional US sanctions should raise reserve managers’ demand, in search for alternatives.

China may not attract as much attention because its currency is still not deliverable. Nevertheless, the micro is important because the People’s Bank of China has been busy enhancing the consumer experience. Data show that transacting in local currency in mainland China is increasingly easier than almost anywhere else in the world. That, in the second-largest economy in the globe, should be in itself a magnet to reserve managers.

Daniel Tenengauzer is Head of Markets Strategy, John Velis is an FX and Macro Strategist and Geoff Yu is a Senior EMEA Market Strategist at BNY Mellon Markets.

Questions or Comments?

Write to daniel.tenengauzer@bnymellon.com, john.velis@bnymellon.com, and geoffrey.yu@bnymellon.com or reach out to your usual relationship manager.