Where the Smart Money is Finding Safety

As losses mounted, where investors found refuge.

Where the Smart Money is Finding Safety

As Losses Mounted, Where Investors Found Refuge

May 2020

By Katy Burne

With investors facing continued uncertainty from the pandemic, many are building larger-than-normal cash positions, with government money market funds and bank balance sheets a preferred destination. The intensity of that dash for cash has surpassed even 2008 levels.

The least glamorous investments on Wall Street have become some of the hottest places to be as investors worry about the unpredictable duration of the COVID-19 crisis and the risk that recent rallies in stocks and other risky assets may be overdone.

That buildup of cash has benefitted money market funds, bank deposits and gold, among other areas. Investors have turned to government money market funds faster than they did in the 2008 collapse, with some funds even closing their doors to new investments.

Financial and non-financial institutions alike have deposited cash on bank balance sheets at a rapid clip. Much of the money is coming from government money market funds, whose managers have cash rushing in and sometimes nowhere else to put it that is generating any yield.

“Historically, trust banks see the biggest deposit increases in times of stress,” said Brian Foran, analyst at Autonomous Research. He put most of the increase in deposits down to a “huge flight-to-safety” and “cash-is-king mentality” among asset managers, as well as corporations drawing cash on revolving credit lines in an uncertain environment.

US Treasuries still appear to be some of the most sought-after securities. A stampede for Treasury bills in March briefly sent their yields into negative territory for the first time in four years. Those yields are still anchored near some of their lowest points of the year, even with the government borrowing to fund more than $2 trillion in economic stimulus packages.

Companies have also paid more than normal to borrow in the commercial paper market. Many non-financial corporates rated A-2/P-2 drew down on their bank liquidity lines and were limited to issuing commercial paper in maturities of one week or less because the volatile market conditions prevented them from issuing debt longer than seven days.

Activity in most markets has stabilized since central banks announced a series of emergency actions in March. The Fed has facilities not just for Treasuries but for everything from highly rated corporate debt and fixed-income exchange-traded funds to mortgage bonds, municipal bonds, commercial paper and bank certificates of deposit.

Those programs are driving rates lower but have also increased the Federal Reserve's balance sheet to more than $6 trillion from $4 trillion as recently as December. Some people expect it to grow to as much as $10 trillion, an unprecedented level.

“Historically, trust banks see the biggest deposit increases in times of stress.”

— BRIAN FORAN, AUTONOMOUS RESEARCH

Nevertheless, even as bargain hunters tiptoe back into stocks and investment-grade companies sell record amounts of new bonds, the majority of investors are still displaying above-average levels of caution.

They have good reason: approximately 25 million were unemployed in the US as of the end of April, roughly 18% of the workforce, but that could rise to as much as 25% by the middle of May, according to BNY Mellon strategist John Velis. The International Monetary Fund is projecting the global economy will contract by 3% this year, worse than during the 2008–2009 meltdown.

Wall of Cash

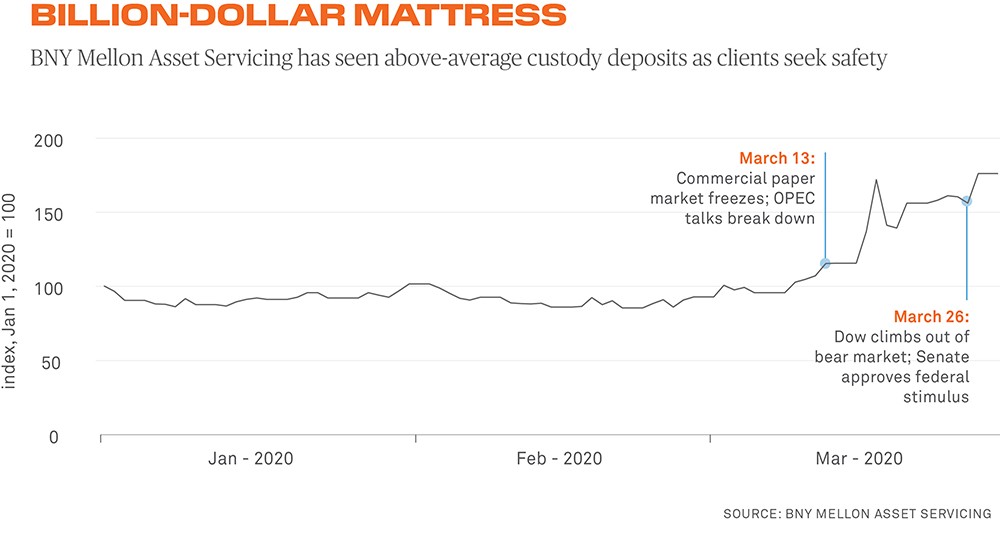

Banks with custody and transaction-banking operations in particular have seen a surge in cash from clients. At BNY Mellon, deposits in the first quarter averaged $258 billion, up 20% from year-ago levels, rising to $337 billion on the last day of March.

“Our clients depend on us not only for our operational expertise and stability, but also because we have a strong balance sheet and are prepared to help with their cash and liquidity needs even in difficult times,” said Emily Portney, global head of client coverage in asset servicing for BNY Mellon.

Similarly, State Street saw average deposits in the first quarter of $180 billion, up 16% year-over-year. J.P. Morgan’s corporate and investing banking unit saw deposits average $562 billion, up 14% year-over-year.

BlackRock's cash-management business saw $50 billion in net inflows in the first quarter as clients de-risked rapidly, the company said.

In many cases, money market funds were stashing cash at banks to avoid buying negative-yielding securities. “Some funds may be able to temporarily park cash at their custodian at some neutral rate, which is a way of staving off negative yield,” said Alastair Sewell, senior director in fund and asset management at Fitch Ratings.

Elsewhere, asset managers were keeping powder dry in anticipation of needing to raise cash for margin calls. Access to liquidity is a big selling point when financial markets are not functioning smoothly, because incoming cash from collateral calls on winning trades often arrives after other counterparties start demanding cash on losing trades.

Liquidity is not the only motivating factor. Some hedge funds have been putting money onto bank balance sheets to sidestep potential counterparty risk from their prime brokers, although this is less of a concern than it was in 2008. “There’s no question that you rely on your third parties far more in moments like this than you do when times are good,” noted Tom Staudt, chief operating officer at Ark Investment Management, an issuer of actively managed ETFs.

While Ark did not need to park cash with banks, Staudt said counterparty risk is a key consideration when picking partners. “For us, BNY Mellon makes that list since we are confident they are a healthy organization in good financial condition, not a niche broker that we have to worry about going under,” he added.

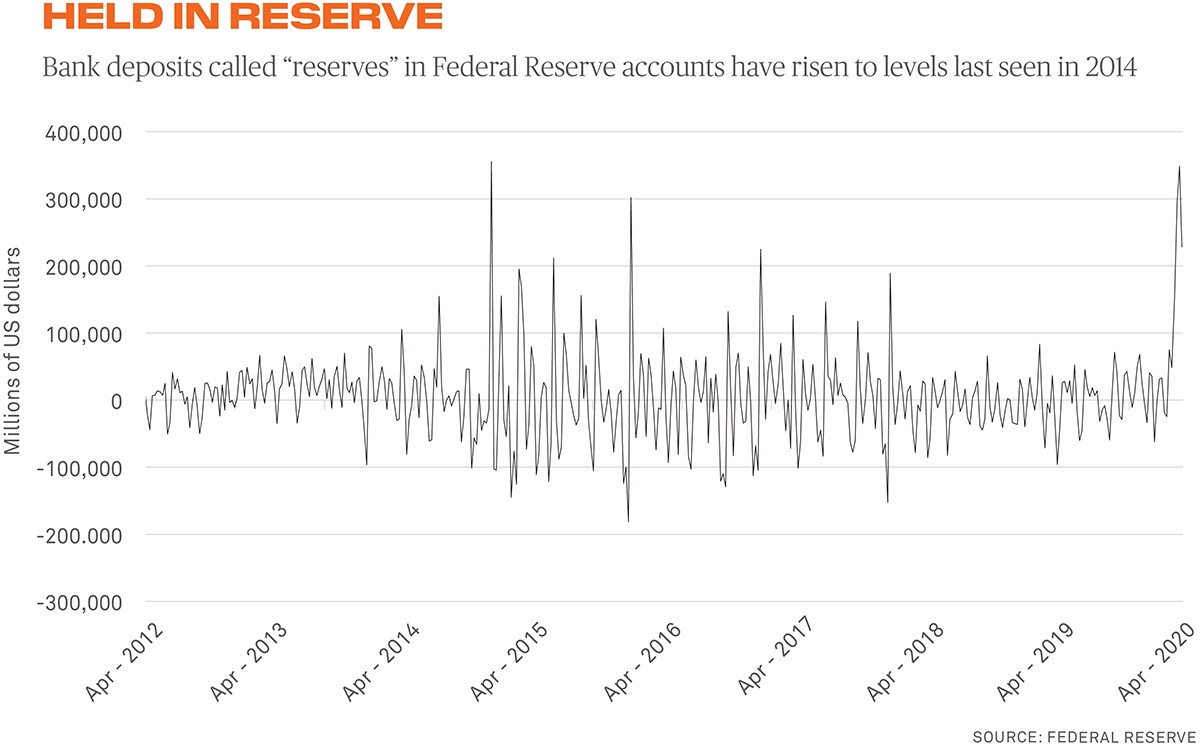

Commercial banks overall have seen clients adding cash to their accounts. The annualized growth rate in bank deposits for March was 42.5%, Fed data show, compared to an average of 6% in the previous 12 months, and weekly data through April 15 show the growth may be faster still. The cash deposits, or "reserves," that banks park at the Fed grew to $346.9 billion in the week ended April 1, the most since 2014, but as of April 22 they stood at $184.5 billion.

The problem is that inflows are coming to banks at a challenging time. Some bank balance sheets are already tight due to post-crisis leverage rules, though most are still open to helping clients manage their cash. Congress anticipated this imbalance and adjusted the supplementary leverage ratio to exempt custody bank deposits at central banks in 2018. The Fed then further expanded that change to a wider pool of banks in March, but the changes may not provide much balance-sheet relief because they are only temporary.

Another issue is that the margin banks make on extending their balance sheet is narrowing. When the Fed lowered benchmark interest rates by 150 basis points in March, it lowered the rates banks can earn on cash they park at the Fed to just 0.1%.

J.P. Morgan Chase told hedge funds in early April it would need to start charging them as of April 17 for US dollar prime brokerage deposits, because of the lower rates. A spokesman for the bank declined to say if the charges were ever implemented. Such charges are rare, but Sewell says, “We find the custodians are only willing to offer zero rates for a short period of time, and after that they would charge.”

Shelter in Place

Perhaps the most dramatic evidence for the flight to safety has been the torrent of money chasing government debt carrying little to no yield, or even the risk of a negative yield.

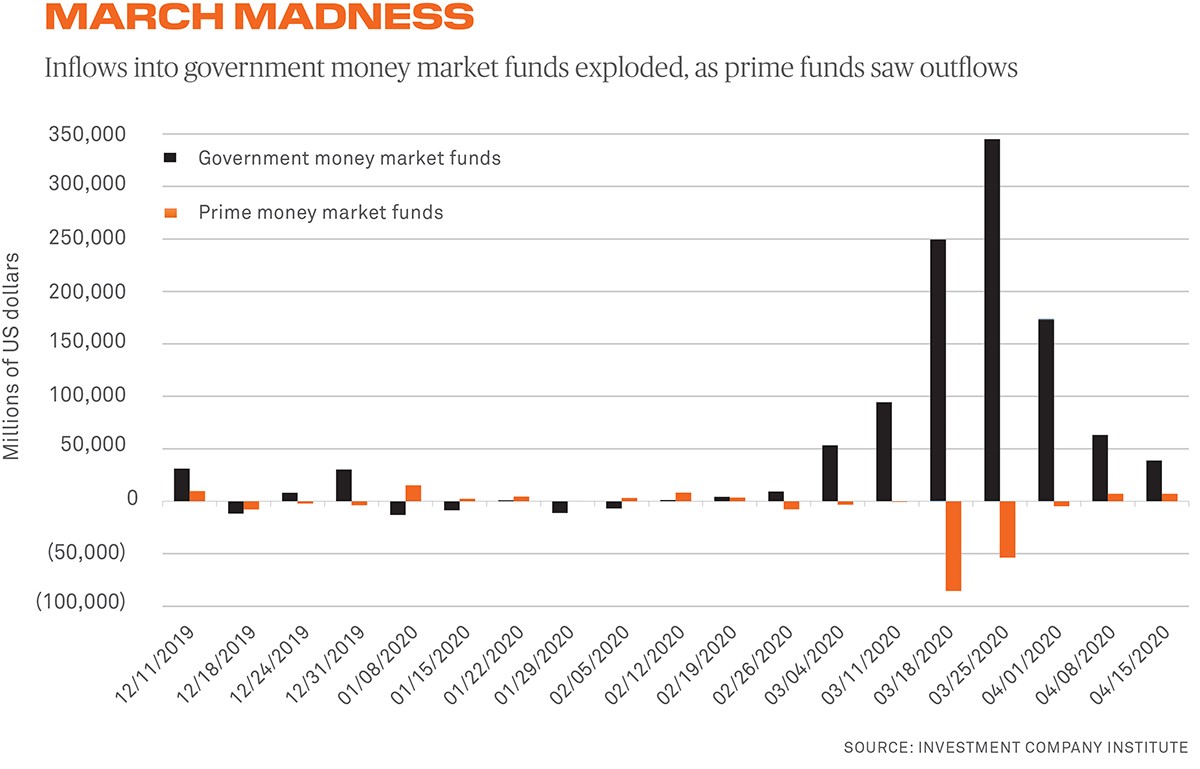

It took just seven weeks for US government money funds to grow by $980 billion as of the week ending April 22, according to the Investment Company Institute. In comparable times of rapid change, it took far longer: 32 months around the time of the regulatory shakeup of money market funds in 2016 and 16 months in the 2008 global financial crisis.

The week ended March 25 was the fourth-largest weekly inflow ever, at $344 billion, ICI said, and the speed of that influx — coupled with the Fed’s rate cuts — “surprised a lot of people,” said Laurie Brignac, head of global liquidity at Invesco.

Vanguard, a $5.3 trillion asset manager, on April 16 said would shut its $39.5 billion Treasury money market fund to new shareholders accounts, citing a desire to protect existing investors from the downward pressure on yields. On March 31, Fidelity also said it would “soft” close certain government-only funds, according to Crane Data.

“Our clients depend on us not only for our operational expertise and stability, but also because we have a strong balance sheet and are prepared to help with their cash and liquidity needs even in difficult times.”

— EMILY PORTNEY, BNY MELLON

The rush into government funds accelerated when they were paying a higher yield than Treasury bills themselves. In late March, the majority of the bills market experienced negative yields, including for debt as far out as December. The last time that happened was 2015.

Yields on one-, three- and six-month bills briefly started rising again in early April as the federal government issued more debt to help pay for its economic stimulus and the delay in federal tax collections. “We were able to get on the phone with the US Treasury to reinforce the need for a lot more cash-management bills,” said Brignac at Invesco. But yields fell again in mid-April and remained at depressed levels through the second half of the month despite robust issuance, indicating safe assets were still in high demand.

As money flooded into government funds, it flowed out of "prime" funds, which buy commercial paper and certificates of deposit. In March, investor desire for liquidity led to nearly $150 billion in outflows, more than double what came out in 2008.

Banks have offered to buy securities from prime funds if they get squeezed by redemptions. BNY Mellon purchased $3 billion in securities from both its own affiliates and third-party money market funds in the first quarter, and continued buying more in early April.

US money market fund assets exceeded $5 trillion for the first time as of April 27, up about $1 trillion year-to-date, with monthly inflows to that point into prime funds now positive again at $75 billion and government funds up $350 billion, according to Crane Data

But some government funds with high expenses are already waiving management fees to prevent their yields going negative.

Moody's Investors Service said in an April 16 note that it expects assets in the Fed’s new money market fund backstop to increase if short-term money market liquidity remains tight and uncertainty over the virus persists. The liquidity facility held $48.8 billion in assets as of the week ended April 22, down from a peak of $53.2 billion on April 8 after the market's initial struggles.

Bizarre Behavior

Some of the keenest signs that traditional havens were not behaving normally were in what are supposed to be the safest investments. In March, traders said several banks were not quoting prices for Treasuries and there were reports of a shortage of physical gold bars.

Rates on commercial paper maturing in three months and longer briefly rose back to levels last seen in 2008, despite the Fed backstop. In the week ended April 16, tier-II issuers only sold a daily average of $1.5 billion in commercial paper maturing in 10 days or longer, compared to $2.4 billion in the week ended March 6 and $868 million in the week ended March 27.

“Although as a Tier II, you are a fairly strong investment-grade company, you were having to play a high wire act” by borrowing over just a couple of days at a time, said Tom Deas, chairman of the National Association of Corporate Treasurers.

Meanwhile, insured cash sweep products have grown by their largest monthly dollar amount in the program’s history, which dates back to 2011. Balances in April were 35% higher than they were at the start of the year, according to Promontory Interfinancial Network, a US network of about 3,000 banks that hold $375 billion in US deposits.

An insured cash sweep is a product that allows investors to federally insure large dollar deposits by placing blocks of cash with multiple banks through one intermediary — BNY Mellon included — at one interest rate. Operationally, the client funds stay on deposit until the client places a withdrawal and the money is put back in their operating account. “With everything happening in the world, safety matters,” said Joseph Hooker, senior managing director at the Promontory network.

“Some counterparties simply didn’t want to trade.”

— ANDY BURGESS, INSIGHT INVESTMENTS

Even repo markets — long a port in the storm for investors wanting to generate a return via short-term US dollar loans collateralized by Treasuries and other securities — have not been able to absorb all the available cash, partly because mass de-leveraging has reduced the demand to borrow.

As a result, rates on repos have lately been comparatively low and even occasionally negative, which is extremely rare in the US. The Fed has an overnight repo facility, which is useful for sucking up excess cash from money markets, but it pays 0% interest, has a 1:15 p.m. cutoff, and a $30 billion cap per fund. Nevertheless, repo remains central to many institutions’ short-term cash investment strategies.

Many funds have been insulating their portfolios by carrying higher volumes of cash, especially as sharp moves continue. Insight Investment's UK Liquidity Fund, for instance, typically runs 30% of its portfolio in overnight cash instead of the 10% required by regulators, but now has 38% in overnight cash.

With traders at counterparties also working from home, “It has made accessing trading teams and liquidity more challenging,” said Andy Burgess, a fixed-income investment specialist at Insight. Markets are far from out of the woods, and memories from the March pullback are all too fresh.

“Some counterparties simply didn’t want to trade,” he added. "We do not rely on market liquidity to try and meet client liquidity needs, which left us relatively well positioned when it dried up."

Questions or Comments?

Write George Maganas in BNY Mellon Markets or reach out to your usual relationship manager.