China Rising: Door Widens to Investors

China Rising: The Door Widens to Investors

Opportunity Knocks as China Transforms

April 2021

By Katy Burne

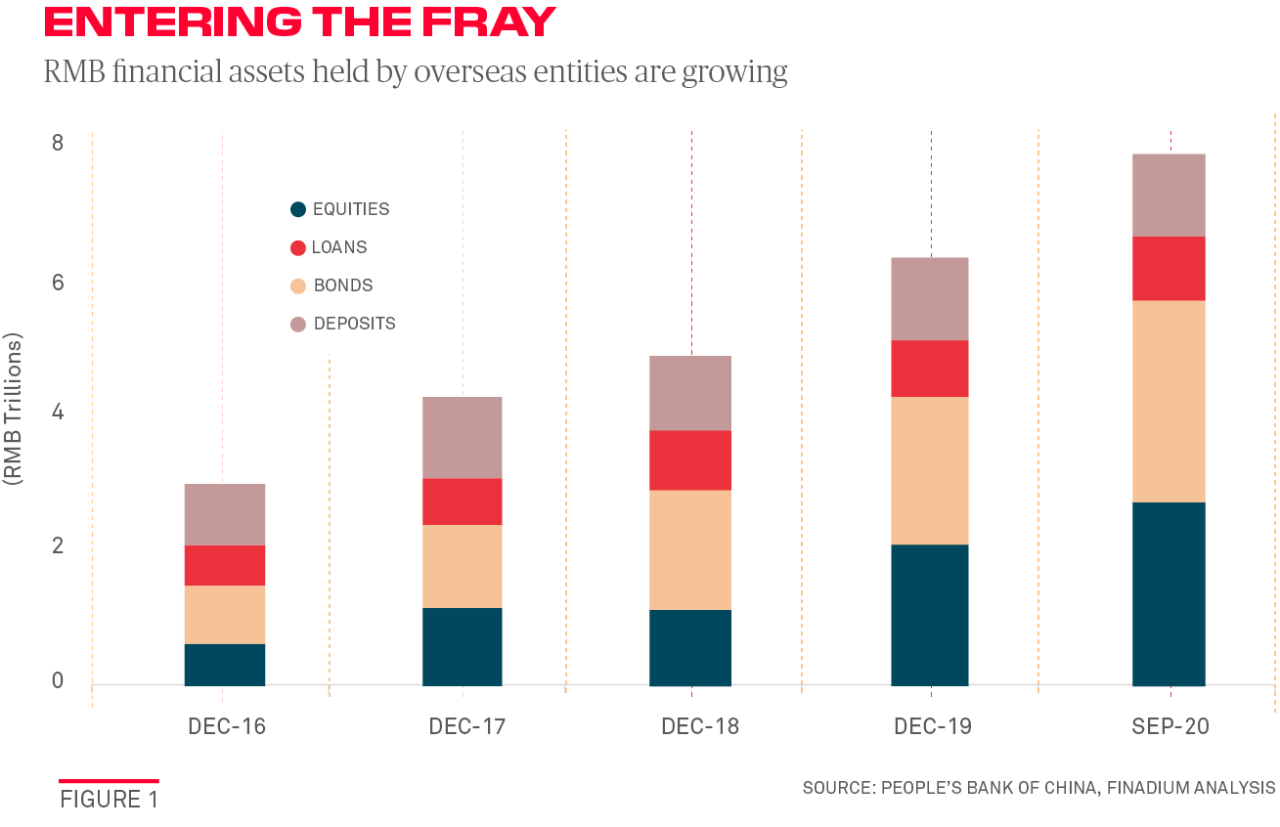

The pace with which China is allowing more sophisticated hedging and financial products is creating new opportunities for foreign institutions, who want greater onshore exposure and collateral mobility.

The liberalization of China’s capital markets has accelerated in recent months, making it easier for foreign money to flow in and out through enhanced cross-border trading schemes, abolished investment quotas and an expanded scope of permissible financial products.

Reform-minded regulators there—who see the benefits of adding foreign institutional capital into the country’s retail-oriented ecosystem—have relaxed foreign-exchange rules, allowed new trade types such as stock lending and futures, and indicated that fixed-income repurchase agreements are coming.

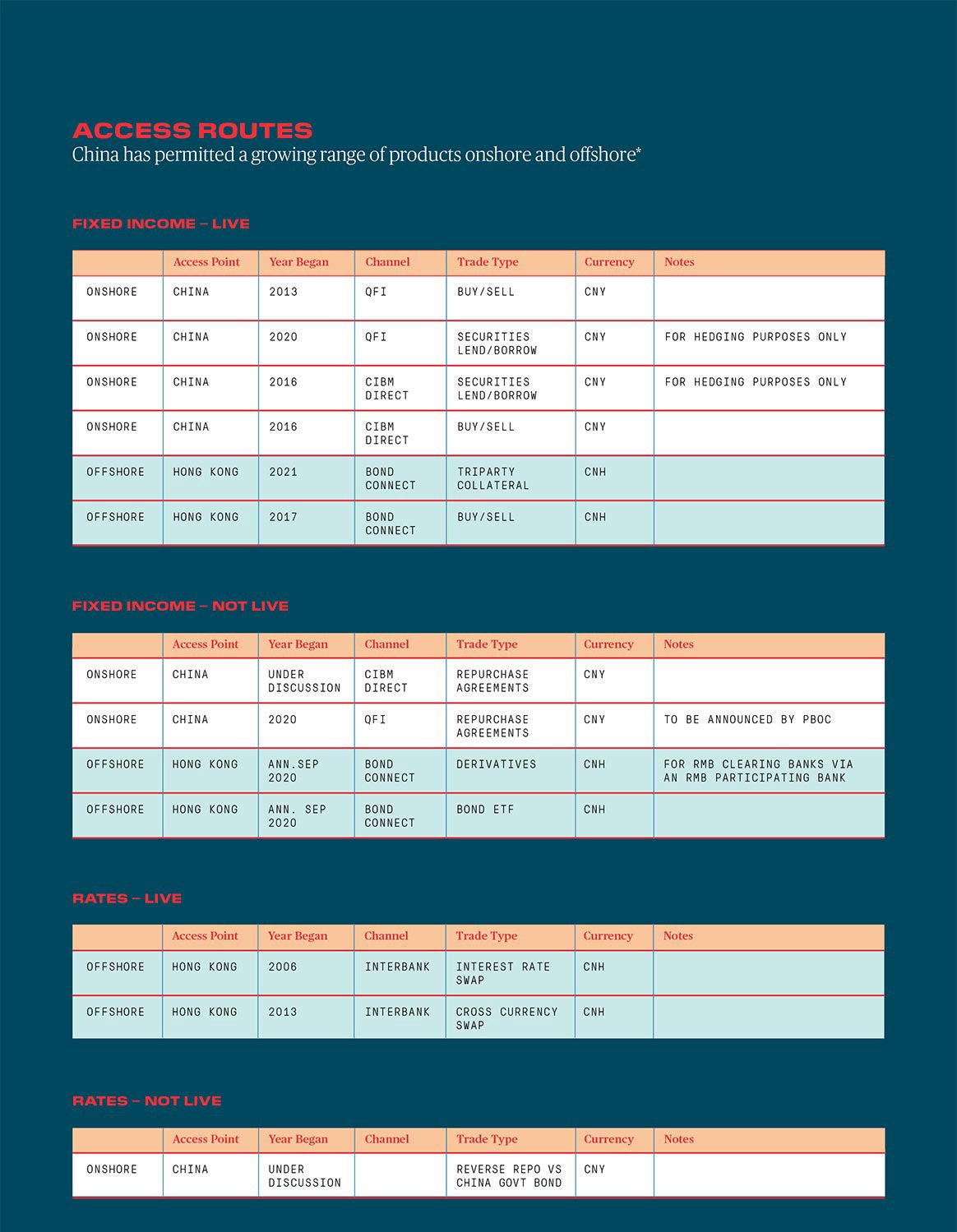

Currently, foreign owners account for only 3% of domestic fixed-income securities in China’s onshore bond market, in part because the country has tightly controlled China’s currency and sought to protect local companies from outside speculators and what they perceive as unstable capital. Now, all that is changing because of global macroeconomic forces that are reshaping its domestic economy (see Figure 1).

“China was the catalyst we needed in Asia,” says Tim Wannenmacher, head of financing and co-head of global markets distribution for Asia Pacific at UBS in Hong Kong. “It has depth and a large amount of trading opportunities, so you could technically deploy a meaningful amount of money there.”

Demand from institutional investors abroad is showing up in the rising number of account openings, daily trading turnover and assets in custody. Many of the new entrants are overseas hedge fund managers, private equity firms and institutional fund managers, seeking either local licenses through the qualified foreign investor (QFI) scheme or offshore gateways that are operated from Hong Kong.

China’s domestic equity and fixed-income markets are already the second largest in the world by market capitalization. Adding to the allure since they opened to foreigners in 2002 are the prospects for growth, a rising middle class that is generating more wealth, a stable currency and attractive returns on bonds relative to rates in developed markets. China’s 10-year government bond yielded 3.2% as of March 19, compared to 1.63% on the comparable U.S. Treasury bond. Improving settlement timing and an alignment of offshore schemes with onshore holiday trading hours have also helped.

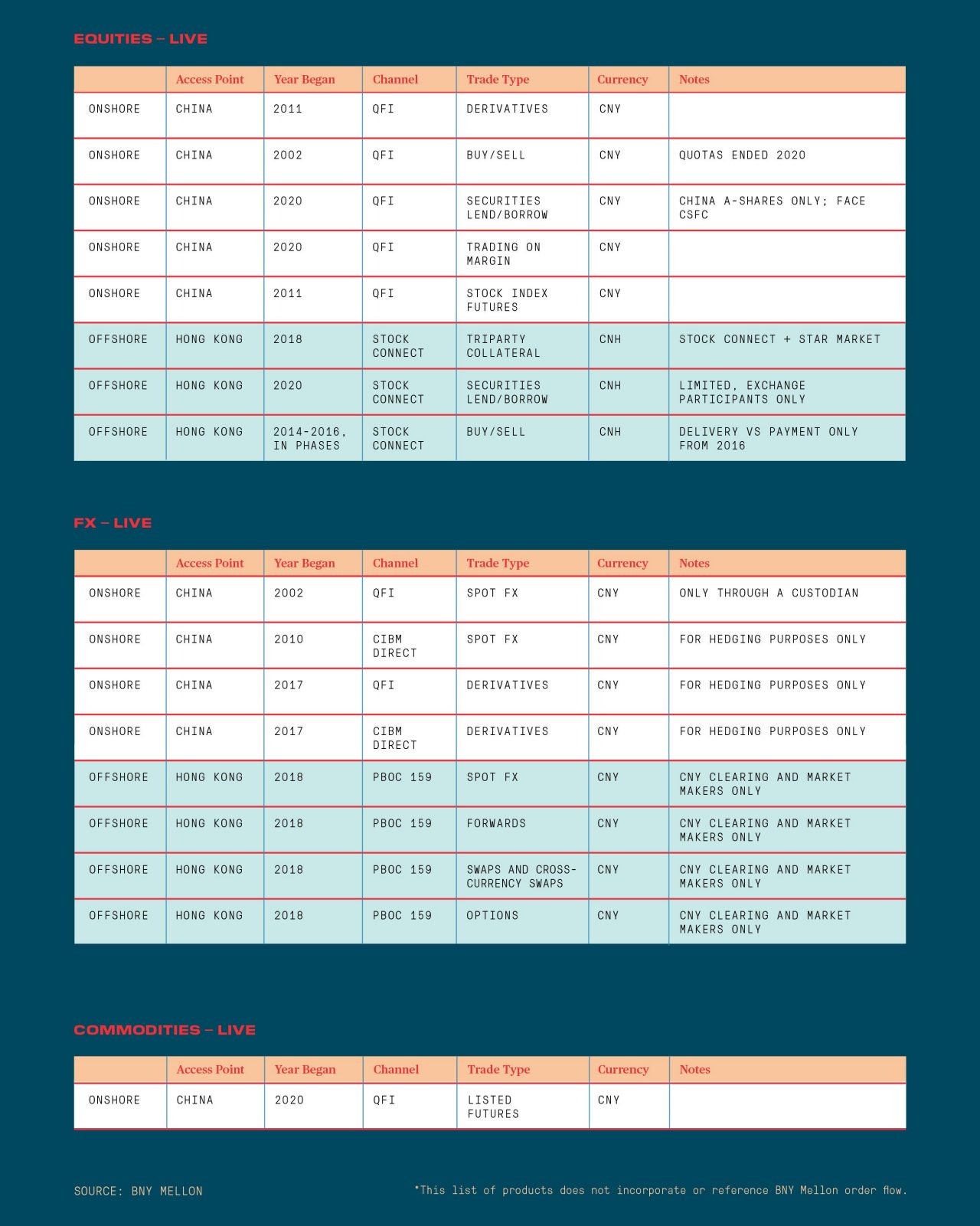

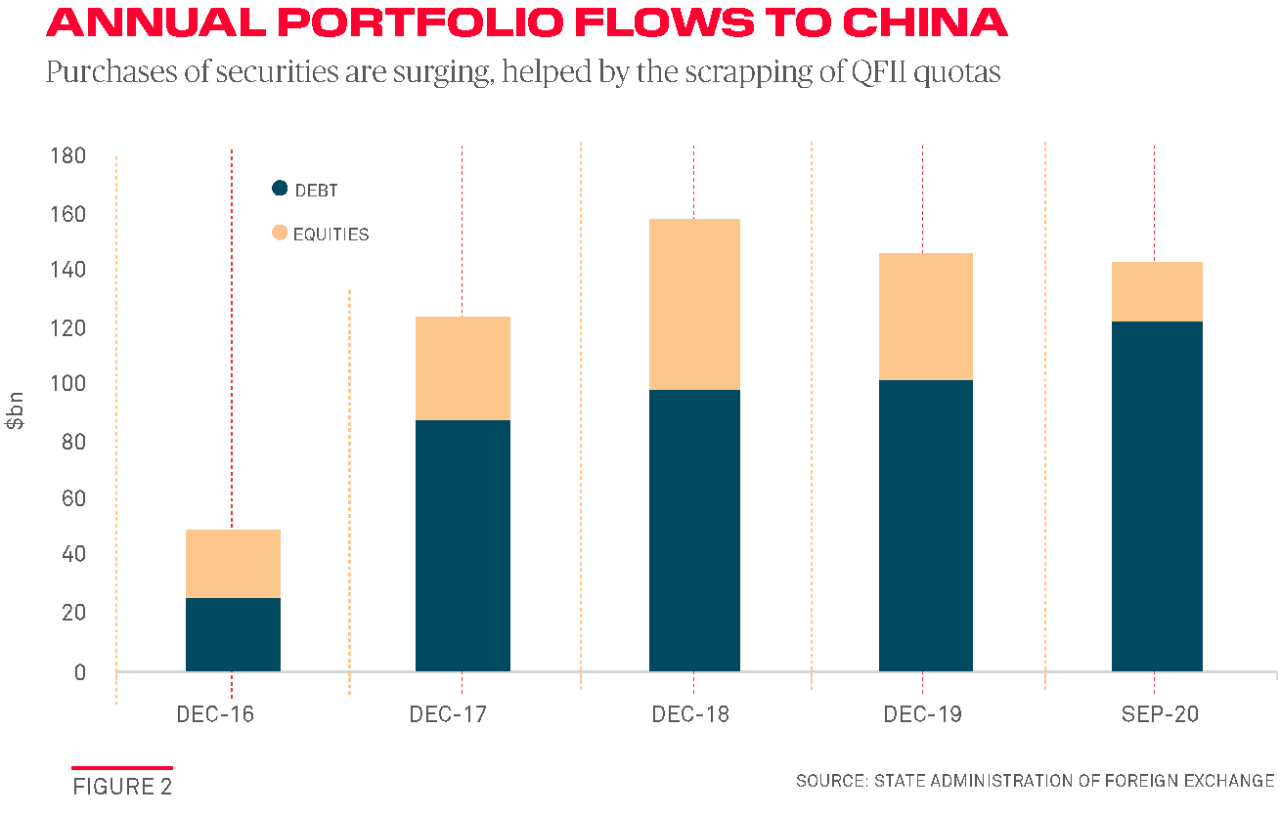

In the first nine months of 2020, China gained $124 billion of foreign portfolio debt flows, more than the $102 billion for all of 2019, according to the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) (see Figure 2). The amount of yuan-denominated assets held by foreign investors is now $1.22 trillion, according to Finadium, up from $459 billion in 2016.

“The instrument selection is widening and giving managers like us a lot of opportunity for offshore fundraising to access the domestic market.”

— Rajeev Mittal, Fidelity International

China’s commitment to opening its capital markets has continued despite recent political developments between the U.S. and China. “The intention to open up the markets and attract global investors appears to be very strong, even with rising geopolitical tensions,” says Lyndon Chao, head of equities and post trade at the Asia Securities Industry & Financial Markets Association (ASIFMA). “They are sophisticated enough to see the benefits of securities lending, but they will make sure they can control and monitor it.”

Connect and Collateral

Chinese regulators have become increasingly flexible because they see that more investors will help the country’s capital markets to flourish and domestic companies to raise cash.

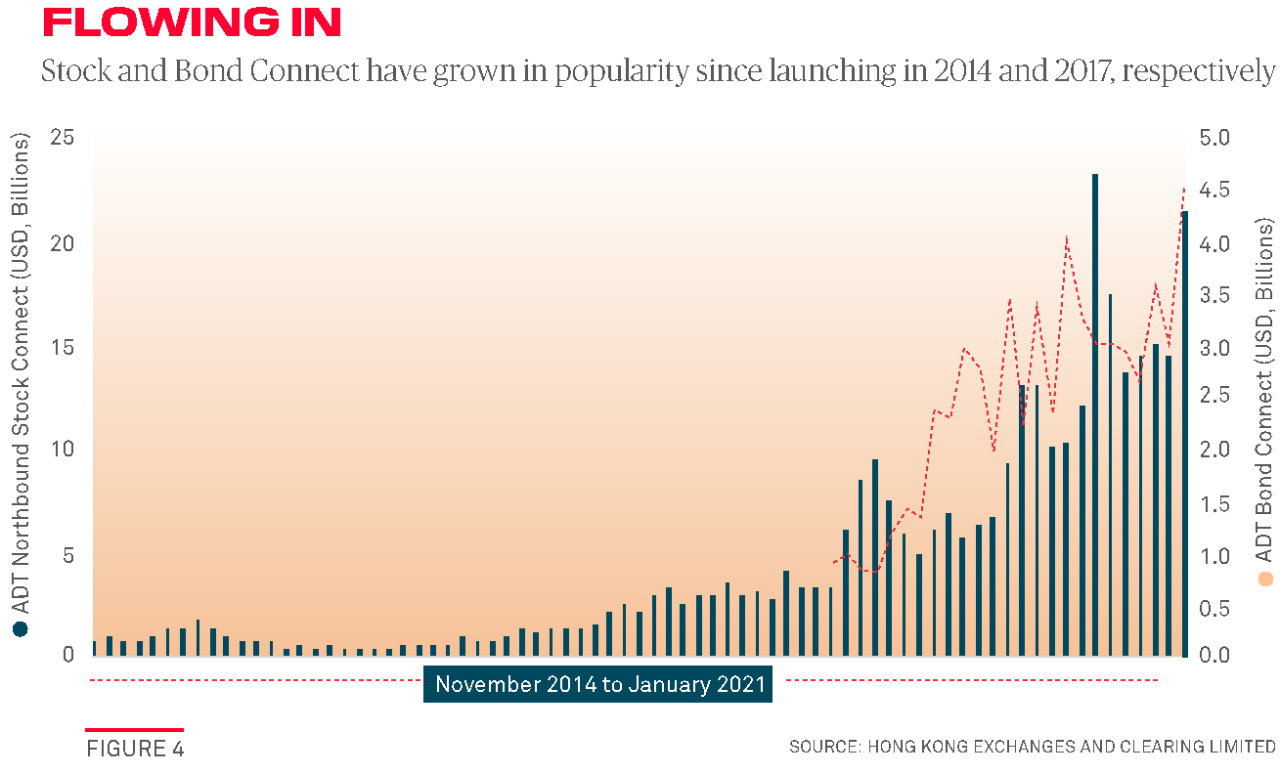

The Stock Connect program, launched in 2014 for foreign investors to access China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges through Hong Kong, this February provided access to eligible A-shares listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange’s (SSE) Sci-Tech Innovation Board (STAR Market). Around $14 billion of foreign investment daily is already coming through Stock Connect into Mainland China equities, according to Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEX) (see Figure 4).

The addition of eligible STAR Market shares in Stock Connect will help international investors expand their investments in biomedicine, technology and e-commerce companies, which are part of China’s growing new economy and which have seen increased investor interest amid the COVID-19 pandemic, says Tae Yoo, managing director in global client development at HKEX.

Bond Connect has separately taken off since launching in 2017. In April, BNY Mellon became the first triparty agent to enable foreign investors to pledge China government bonds as collateral. Previously there was no mechanism to finance bonds purchased through Bond Connect, but balances of Stock Connect collateral in triparty have increased more than 150% over the past year. “We already see increasing market take-up in being able to use China Connect stocks as collateral in triparty, so it’s logical to think we will see the same with Chinese bonds,” says Karen Lam, a partner at Linklaters in Hong Kong.

Dealers have sought the ability to use China government bonds as collateral for years because if those firms are sitting on inventory, without it being monetized, those bonds are trapped on their balance sheet and can prove costly when static. Meanwhile, receivers are likely to want to lend cash in exchange for China government bonds given the premium return that may be attainable when compared with other collateral markets.

“With [Stock and Bond] Connect securities representing a growing share of banks’ balance sheets, the focus on identifying solutions to use these securities, including as collateral in financing transactions, continues to increase across the market,” explains Nehal Mehra, global co-head of cross asset financing with global markets at Goldman Sachs.

“It’s a solution that allows for a triparty model to work with existing Bond Connect nontrade transfer restrictions, and once clients see that, there will be significant demand.”

— Nigel Rangel, HSBC

Regulations prevent Bond Connect investors from using more than one custodian, despite this being recently relaxed for QFIs. As a result, BNY Mellon had to develop a custody agnostic solution in which it reflected the bond holdings in the global triparty system, whilst not directly holding them in its own custody network. It also developed a solution with trading platforms in case the borrower defaults. Combined, these hold the promise of many new ways to use China fixed-income collateral globally.

“It’s a solution that allows for a triparty model to work with existing Bond Connect non-trade transfer restrictions, and once clients see that, there will be significant client demand,” says Nigel Rangel, senior product manager for banks and broker dealers within Markets and Securities Services at HSBC.

QFI and Related Reforms

Other deregulatory efforts have allowed the foreign institutional investors licensed onshore to trade on margin, lend or borrow China A-shares through onshore brokers and custodians, and to transact in new financial and commodity futures as hedging tools for the first time.

“We’ve seen huge momentum from global investors seeking to take advantage of China’s market deregulation, through our custody, FX and collateral management platforms,” says Sam Xu, China Country Executive at BNY Mellon. “Firms who prove agile enough to capture these long-awaited opportunities in securities finance, collateral efficiency and hedging can get a meaningful edge in their execution.”

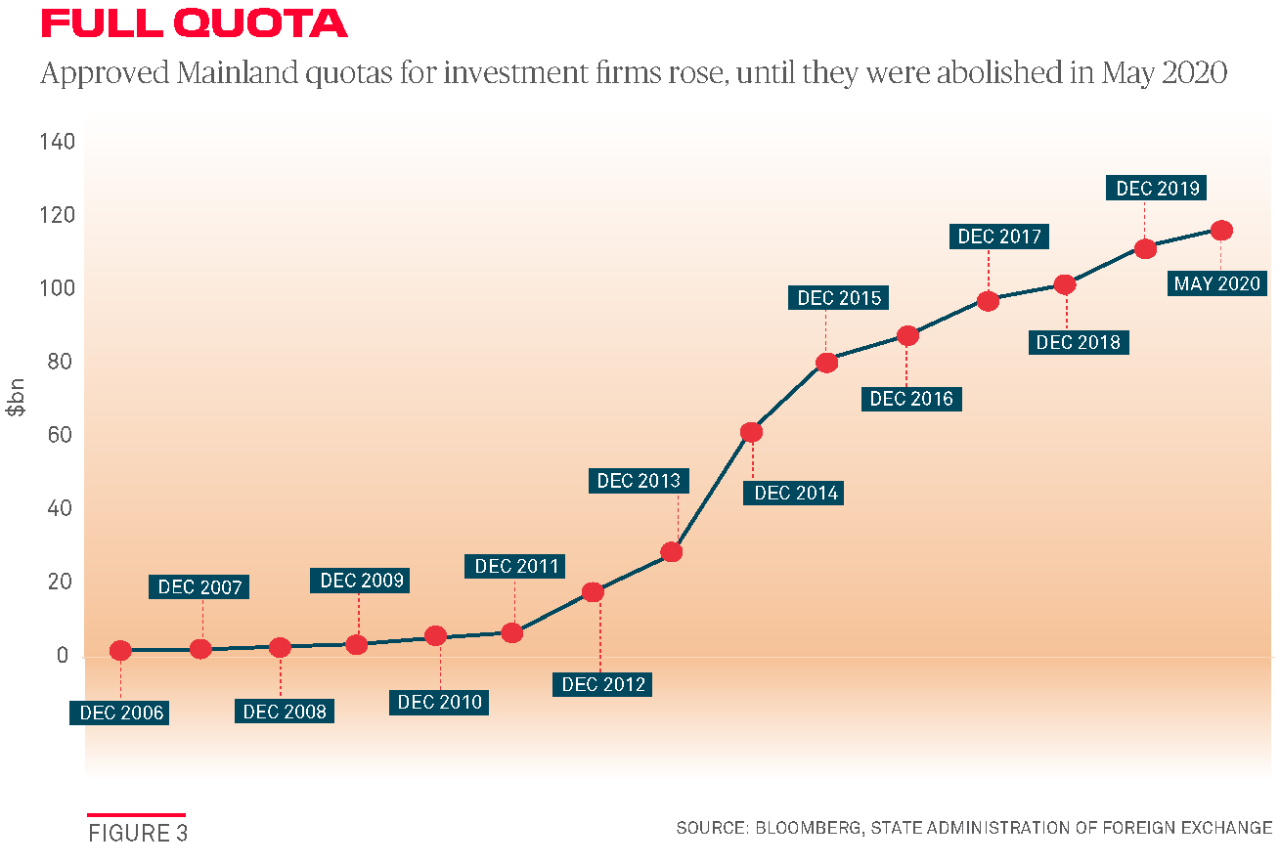

Last year, authorities in China merged the separate Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) regime with a sister one for renminbi investments (RQFII), creating a unified QFI channel. They also abolished fixed investment quotas and removed limits on the number of brokers QFIs could use for fixed income and equities. (Approved quotas had risen to $116 billion right before they were abolished, up from $87 billion at the end of 2016, Bloomberg data show. See Figure 3.)

“We’ve seen huge momentum from global investors seeking to take advantage of China’s market deregulation, through our custody, FX and collateral management platforms.”

— Sam Xu, BNY Mellon

The issue is that until the reforms speed up even more, multiple access channels will continue to operate side by side to encourage the broadest possible participation while the specifics are ironed out. The Stock and Bond Connect schemes have been so successful, for example, that local players see the government aiming to even the playing field between those channels and the QFI scheme.

“The Connect [channels] will not be allowed to outpace direct access,” says Stuart Jones, chairman of the Pan Asia Securities Lending Association, or PASLA. “Whilst the Connect scheme has been a hugely successful program, there is little desire to see flows leave the QFI channel for Connect. QFI reforms will open up a lot more opportunity with offshore funds being able to access more products and trade them directly.”

There also remains plenty of work to do before offshore investors can get the full extent of access that they want through the QFI regime, while not being physically located in China. “They would like to have more choice, like short selling, bond repo and exposure to government bond futures,” says Natasha Xie, partner at law firm Junhe.

The small number of QFIs who are lending or borrowing China equities are engaging directly with beneficial owners. But the new reforms come with mechanisms that are not aligned with international practices. For example, equity lending and borrowing have to be conducted through the China Securities Finance Corporation (CSFC), which prescribes that collateral is ring-fenced by the borrower and does not allow an offshore custodian to be part of the clearing process. The CSFC can also demand 150-200% of margin for stock borrowing.

“They launched QFI access to stock borrowing and lending at the end of December and so there are teething issues,” says Chao at ASIFMA. But it is nonetheless important progress. Some participants have continued to conduct their securities lending activities and hedges from offshore synthetically, via derivatives, until the kinks are worked out.

Meanwhile, eligibility for stock lending among offshore asset owners using Stock Connect is restricted to exchange members, although it is understood that regulators see the benefits of permitting this if they can control aspects of short selling that they view as harmful.

Added to that, China has no concept of agency lending in securities finance. When an offshore institution wants to finance the Stock Connect shares in their inventory to generate cash, they either do so as a principal using their custodian for support, or they pledge the China A-shares acquired under the Stock Connect scheme, in which case the shares are held by triparty agents.

A lack of global offshore holders negatively impacts liquidity, but it doesn’t seem to have prevented securities lending volumes onshore rising 1,025% from October 2019 to October 2020, according to Finadium. The current $20 billion of equities borrowed is dwarfed by the $11.4 trillion market capitalization of shares listed across the Shanghai Stock Exchange ($6.5 trillion) and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange ($4.9 trillion).

“The lack of support for an agent lending concept means a substantial number of foreign investors will be unable to participate, because they don’t have the ability to handle reconciliations, taxes and other aspects of securities lending,” says Wannenmacher.

Gathering Momentum

By far the biggest catalyst for the opening up of China has been its inclusion since 2018 in major equity and bond indices by the likes of MSCI, FTSE Russell and Bloomberg Barclays, which are heavily tracked as benchmarks for passive investments such as exchange traded funds (ETFs).

Another major event was China’s inclusion in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) “special drawing rights” basket alongside major reserve currencies such as the U.S. dollar and euro, providing more weight to those considering Chinese debt as a form of highly liquid assets in their portfolios.

“With the index inclusions, you saw a wave of capital moving in and now the direction of travel is only upwards,” explains Rajeev Mittal, Fidelity International’s head of APAC ex-Japan. In 2017, the firm became the first offshore asset manager to get a private fund qualification allowing it to sell private funds as investment solutions on the mainland, and last year it applied to build a full-scale manager onshore after foreign ownership caps were lifted.

The pace of change has been even more remarkable because it came as growth elsewhere was interrupted from the pandemic. “As many markets closed in, China was opening up,” notes Mittal. “The instrument selection is widening and giving managers like us a lot of opportunity for offshore fundraising to access the domestic market and cater to investors sitting outside of China.”

The limited access to hedging solutions, however, remains an impediment for global hedge funds who run low net exposures, rather than one-directional portfolios. Currently, offshore funds are not allowed to engage directly in equity or interest-rate futures, only a limited set of internationalized commodity derivatives. Even their currency hedges have to be linked to CNH, the offshore version of the yuan.

“They are sophisticated enough to see the benefits of securities lending, but they will make sure they can control and monitor it.”

— Lyndon Chao, ASIFMA

Access to CNY, the onshore yuan, also remains limited for foreign-owned firms, so hedges of Mainland China bonds and equities can be costly relative to trades denominated in CNH because of liquidity constraints. A new circular announced in 2018 called PBOC 159 is designed to resolve those hedging issues by giving institutions license onshore—through the China Interbank Bond Market (CIBM) and QFI channels—to buy or sell CNY.

BNY Mellon, which has been licensed to trade spot CNY since 2011 and CNY forwards and swaps since 2014, has been building its own desk to cater to those changes.

China’s central bank has also steadily advanced work on cross-border use cases of a digital yuan and sustainable investing among asset managers with environmental, social and governance (ESG) mandates. These hot new areas, combined with the recent reforms, could herald a new era in China’s ability to attract foreign sources of capital.

The question remains how much capital, when some of the particulars such as timelines and caveats are yet to be announced by the authorities. Global investors are aware that these guardrails could take time, given that domestic and external macro developments may impact the Chinese reform agenda.

Katy Burne is Editor-in-Chief of Aerial View Magazine in New York.

Questions or Comments?

Write to Daniel Larner in Clearance and Collateral Management; Michael Davies for BNY Mellon Markets; or reach out to your usual relationship manager.