The Changing Face of Dutch Pensions

The Changing Face of Dutch Pensions

Transitioning away from defined-benefit plans

September 23, 2021

By John Hintze

Pension funds in the Netherlands are grappling with a government-led overhaul, which is forcing them to provide unprecedented choice and push more risk taking on plan members.

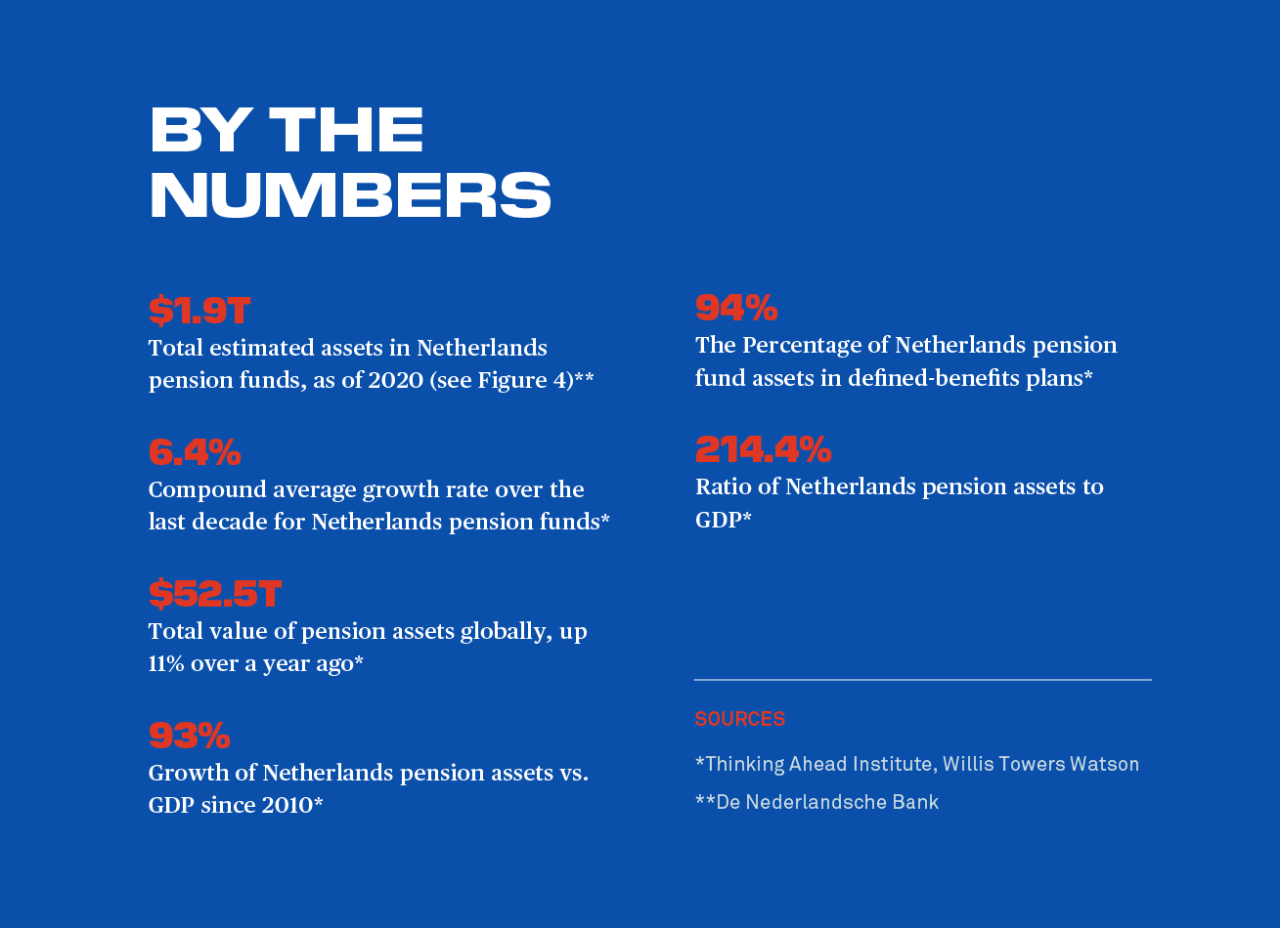

The Netherlands is pursuing a first-of-a-kind transition to put its $1.9 trillion pension system on a more sustainable path. The move offers plenty of scope for opportunity, but also carries its fair share of risk, as well as the need to communicate more actively with plan members.

The government proposal to de-emphasize mandatory defined-benefit (DB) plans in favor of defined-contribution (DC) plans, in which participants shoulder the risks for their own retirement, will require a massive overhaul.

Nevertheless, historically low—and even negative—interest rates over the past decade have fueled the urgency for change because many funds have seen their ability to maintain current payouts dip to precarious levels.

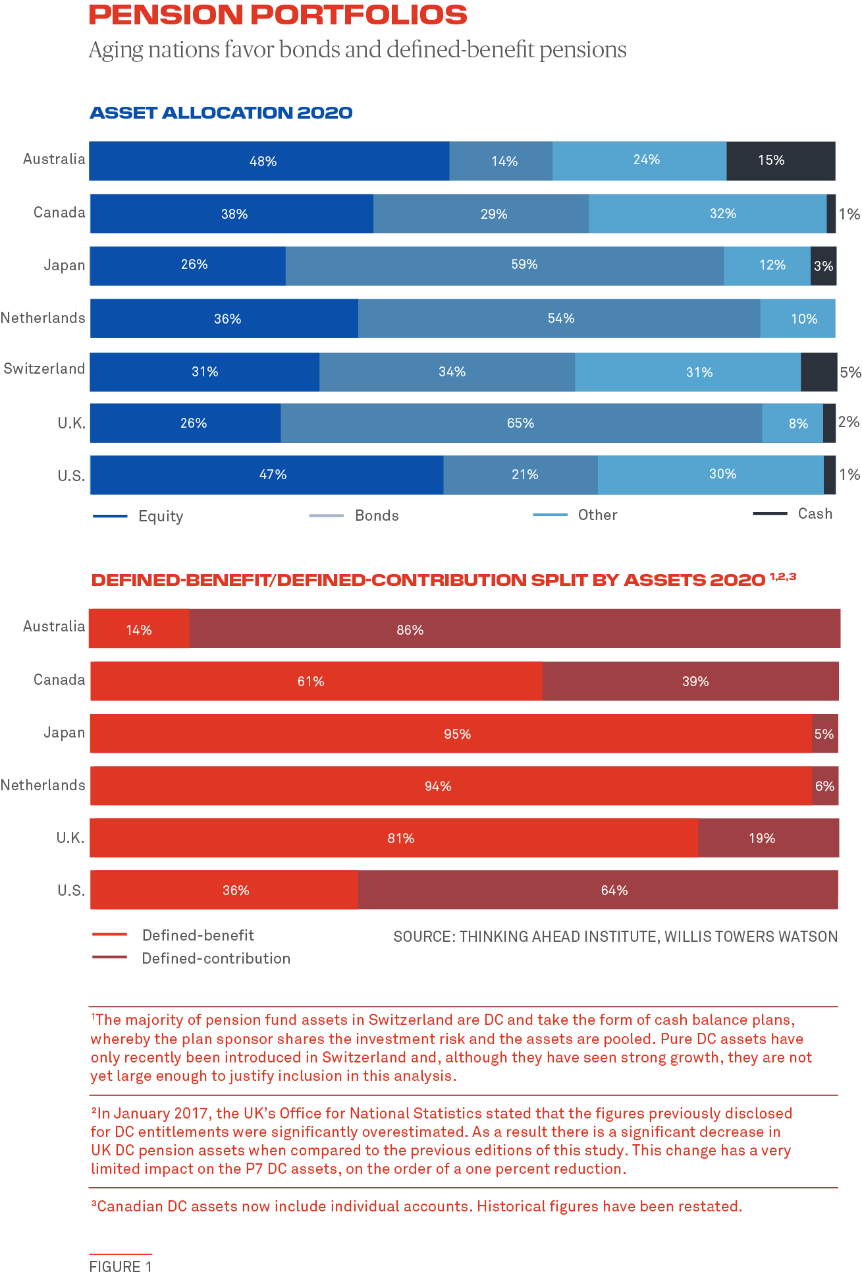

There are other reasons the Dutch need to get the transition right. Firstly, some 94% of domestic pension-plan participants' assets are in defined-benefit plans, which guarantee retirement payouts, according to the Thinking Ahead Institute, a nonprofit think tank at Willis Towers Watson. That is meaningfully higher than the 61% for Canada, 36% for the U.S., or just 14% for Australia, but more in line with neighboring countries like the U.K. with 81% (see Figure 1).

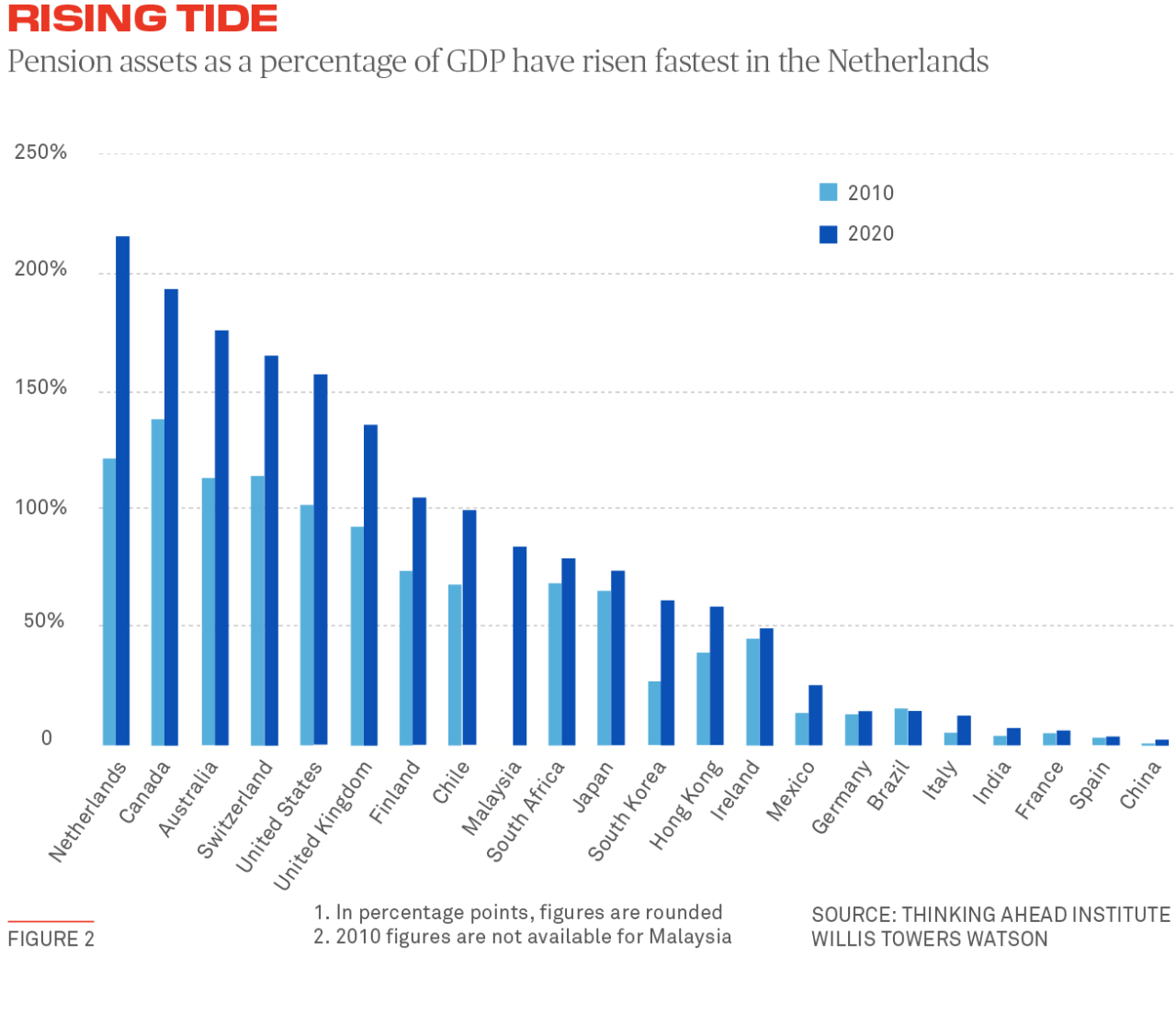

Secondly, the value of Dutch pension plan assets is double the size of the local economy (see Figure 2). The country’s ratio of pension assets to GDP is 214% when most of the 22 countries analyzed by Thinking Ahead have ratios under 100% and many of them offer other means of retirement saving. In some respects, the Netherlands could be a poster child for other countries that are transitioning or aiming to transition away from defined-benefit plans, including Japan, Canada and the U.K.

Typically, in such transitions, defined-benefit plans are closed to new members and their assets and liabilities are wound down while new participants begin in the new defined-contribution schemes. The Netherlands’ initiative is more challenging because the current plan’s holdings will be transferred wholesale into one of the two new schemes offered.

“It’s very unique and hasn’t been done elsewhere,” says Tjitsger Hulshoff, who is heading up the pension transition efforts at APG Asset Management, the largest fiduciary asset manager in the Netherlands. “We’re going to need to provide more frequent information and insights, as well as performance measurements.”

The uniqueness of the proposal has resulted in public skepticism, especially because the Dutch pension system has routinely ranked as one of the best in the world for its overall adequacy, according to Hans van Meerten, chair of Utrecht University’s pension-law department and advisor to the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA), a European Union financial regulatory institution.

He notes that, while the change has been in the works for a decade, the authorities haven’t fully explained why it is necessary. “People didn’t see the need for this huge transformation,” van Meerten says.

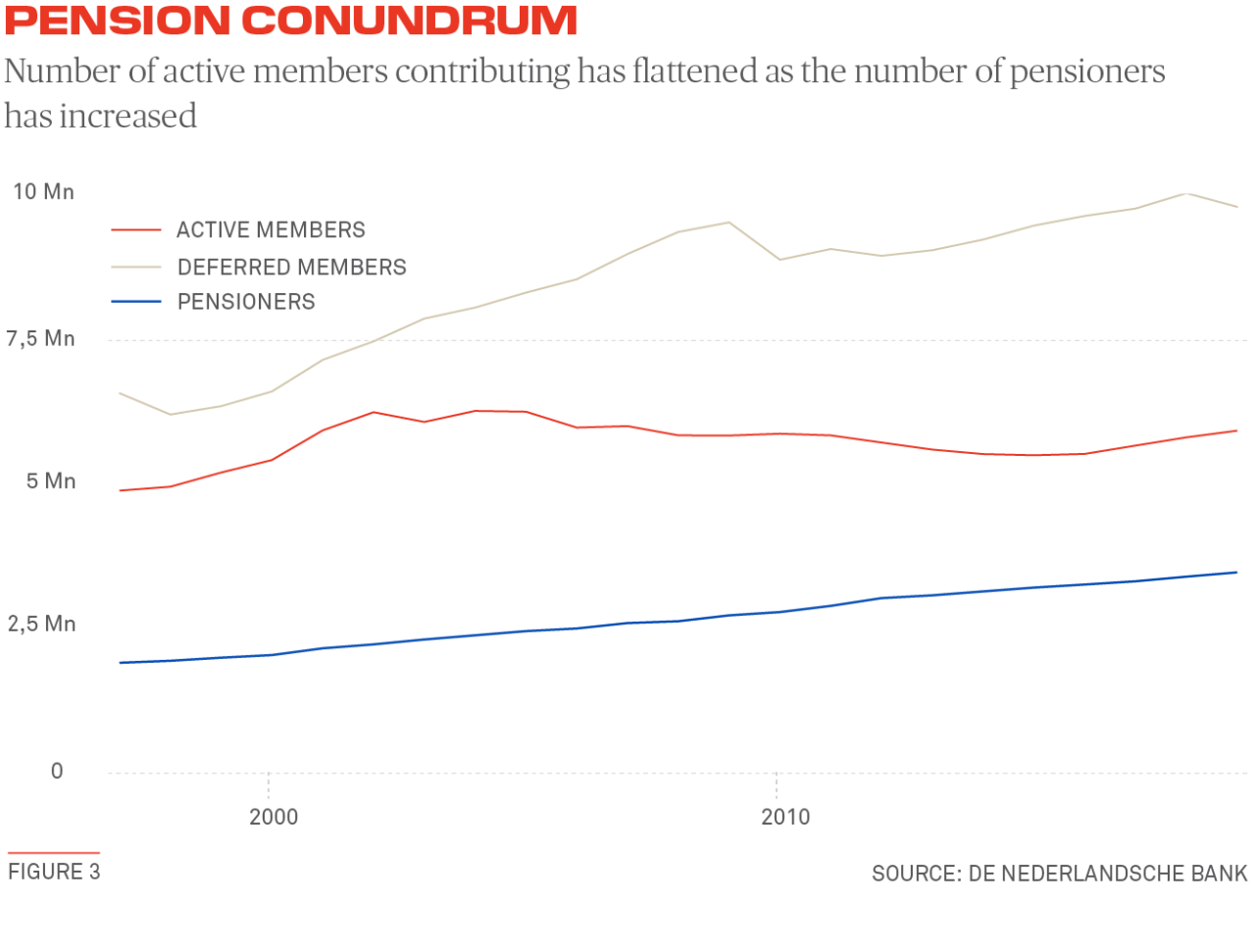

That isn’t stopping the economic realities hitting home. In a report last year, the consultancy Deloitte noted the solidarity between younger and older generations has eroded over time, in addition to employees switching jobs more frequently. At the same time, the number of pensioners is increasing as the number of workers contributing remains static (see Figure 3).

Changes in Store

Whether or not the overhaul is warranted, it is progressing through legislative channels. The Dutch “Demissionary” Minister of Social Affairs and Employment, Wouter Koolmees, confirmed in early May to Parliament that, following negative public comments on the bill, he intends to send a revised version to the Lower House early next year. As such, it will likely become effective no later than Jan. 1, 2023, a year after originally planned. Final implementation of the new pension system has also been delayed by a year, until Jan. 1, 2027.

The delay has come as a relief to many pension funds and their administrators as well as employers and employee unions, referred to as social partners, who must determine the best type of plan for their constituents. But it is also a stark reminder of the complexity of the effort ahead.

The transition will require sweeping changes to technology and administrative systems as well as new investment management and hedging strategies. Among the biggest challenges will be educating plan participants to more actively monitor their pension benefits— requiring pension funds to communicate with them in new ways.

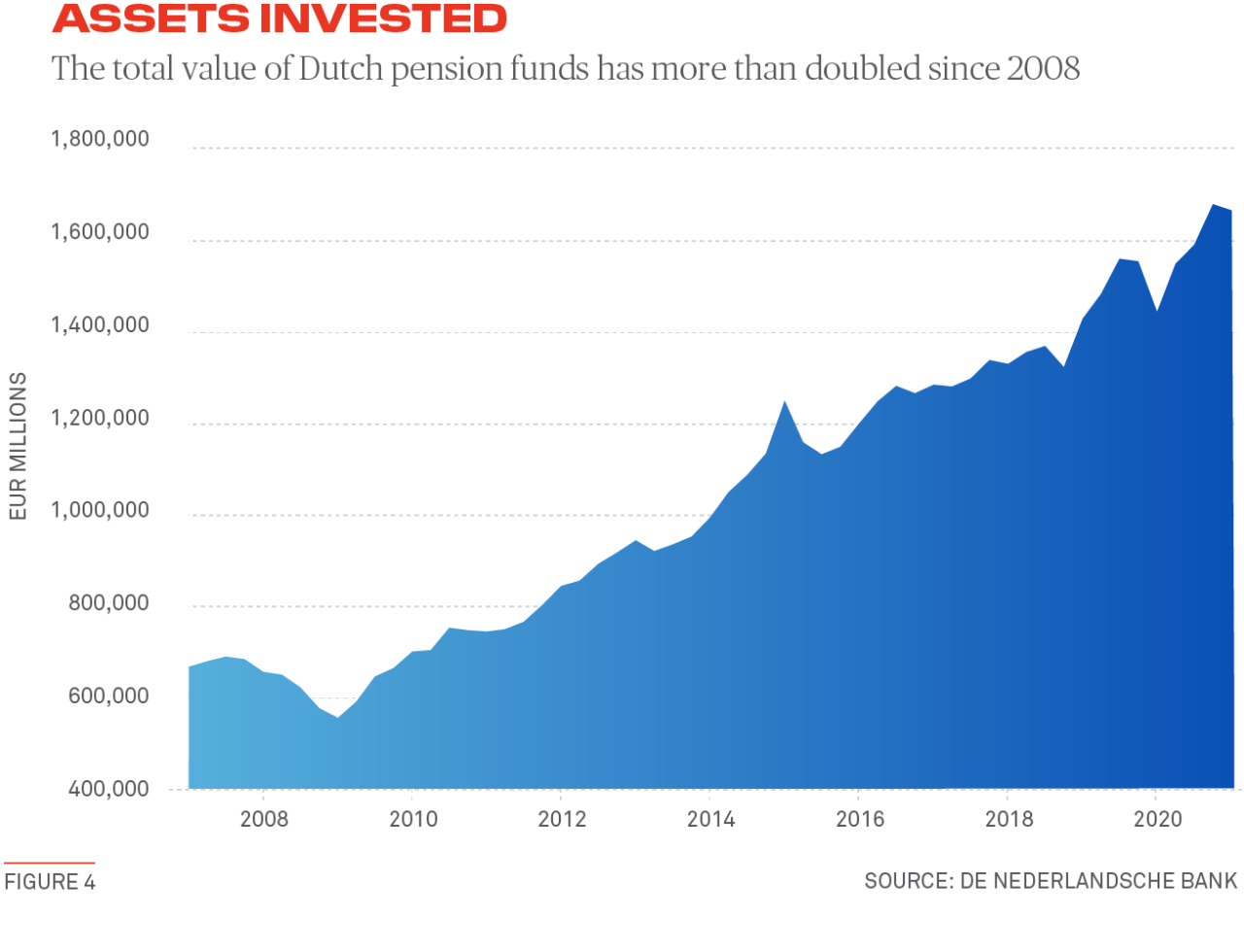

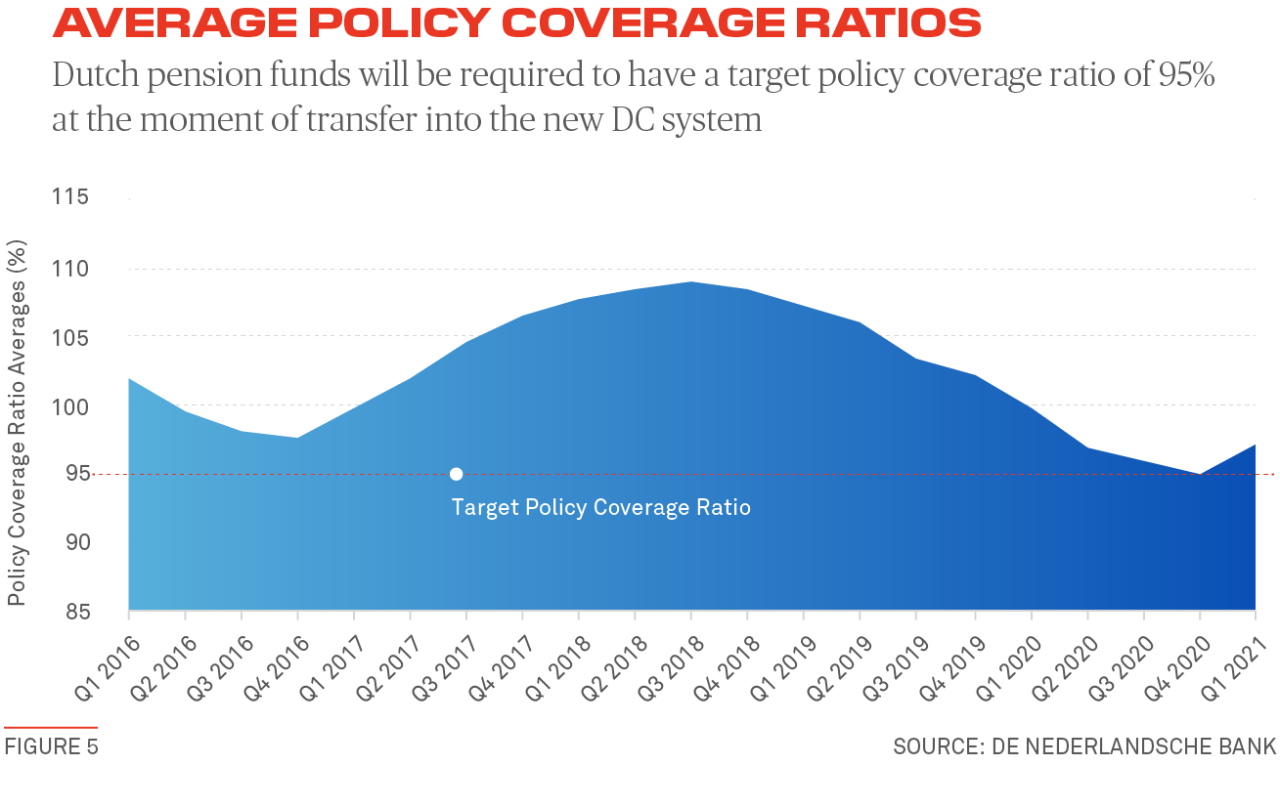

Fundamentally, the draft bill seeks to shift the Netherlands’ defined-benefit pensions to defined-contribution plans, which see participants fund their own retirements with flat contribution rates up to a still-to-be determined maximum. Dutch pension funds will be required to have a target policy coverage ratio of 95% at the moment of transfer into the new DC system (see Figure 4).

The big difference between the current and proposed plans is that the defined-benefit plans provide a pension guarantee but little transparency, whereas in the new ones participants shoulder the risk on their payouts but can track the value of their pension-plan assets and directly influence choices over their investments.

The pension overhaul itself is currently in a fairly uncertain period, following elections in mid-March that thus far have not yet resulted in the formation of a new cabinet. The current demissionary setup puts existing leaders in a caretaker role as they rework the draft and prepare to hand it over to another cabinet. But changes to the legislation are not anticipated to alter the current framework of a move to two types of defined-contribution accounts.

The first new offering, the Nieuwe Pensioen Contract (NPC), will be most similar to the current system because pensions will make investment decisions for their participants, investing premiums collectively and allocating returns to their personal accounts. The NPC plans also will have different risk profiles and a mandatory “solidarity” reserve of up to 15% of the fund’s assets to buffer steep drops in fund asset values.

The second offering, known as the Wet Verbeterde Premieregeling (WVP) plan, will more closely resemble defined-contribution plans in other countries. Participants will be asked to define their risk preferences in line with their age and other life-cycle factors, helping pension funds to define specific investment strategies for them, and whether they want a solidarity buffer at all.

The main difference is that WVP plans provide more freedom of choice, whereas NPC plans rely entirely on the fund to make the investment decisions, says Sacha van Hoogdalem, managing director at Ortec Finance, which provides technology and advisory solutions. Experience in other countries suggests the vast majority of participants end up following the default life-cycle investment strategies set by the pension-plan boards, she notes.

What both types of new plans have in common is how they provide transparency into how the assets are performing. Whereas today investors receive letters annually or quarterly that explain their rights to eventual retirement payments, the new system is a defined contribution plan, in which participants will gain insight into the development of their savings.

That may not sound like a big leap for those accustomed to 401K and IRA accounts in the U.S. or Self-Invested Personal Pension (SIPP) funds in the U.K., which provide multiple investment options and the ability to switch investment strategies. But it is a huge change for most Dutch stakeholders. Communication will be a top priority, especially early on during the transition.

“Now we tell pension participants what they can expect in retirement—their defined benefit—and in the future it will be what is happening to their personal savings accounts and the results we have delivered to that account,” said Maarten Roest, CIO of the ABN Amro Pension Fund, which oversees €34 billion in assets.

“We’re going to need to provide more frequent information and insights, as well as performance measurements.”

— Tjitsger Hulshoff, APG Asset Management

Decisions to Make

Other critical issues that must be addressed include shifting legacy assets and liabilities to the defined-contribution schemes, and adapting systems and processes to provide the necessary transparency. Pension funds must also consider how their investment and hedging strategies may change, as well as how they impact their collateral and securities financing activities.

As of August, securities lending by Dutch financial institutions represented a relatively small percentage of the total assets being loaned out in BNY Mellon’s global securities lending pool, with loans by Dutch lenders being significantly weighted towards fixed income assets. On the other hand, Dutch clients were lending a larger share of their inventories than lenders domiciled in other countries.

If the pending pension regulations seek to amend what institutions can or cannot lend going forward, it could drag on local pension fund performance. Companies’ decisions about how to act on this will hinge on what the final legislation looks like, but they can begin taking steps in several important areas.

While social partners must ultimately decide which type of plan to offer participants, the pension providers (pension funds, insurers) will be responsible for putting it in place and administering it. Consequently, they must effectively explain to participants each plan’s pluses and minuses.

Roland de Greef, an attorney at Dutch law firm Houthoff, said pension funds must thoroughly explain what will happen, both to the overall fund and to individual members. And they must show the impact on individual employees under various circumstances, including economic changes, different interest rates and investment results.

Furthermore, employers must also give individual employees the opportunity to consult with an advisor. If an employee’s current pension right is determined to be higher than under the new defined-contribution scheme, then he or she must be compensated and that must be clearly explained as well, de Greef says.

Employers—likely in cooperation with the pension fund—will seek to look at the group as a whole to calculate the compensation, he added, “but from a legal point of view, individual employees will always have the possibility to ask how this change will impact their specific situations and can ask for compensation.”

“Under the new regime, many pension funds will probably show less demand for fixed-income assets at the longer-end of the yield curve, particularly those with younger plan participants.”

— Marijn Jansen, Achmea

Under the new schemes, participants will own their pension-plan accounts rather than having amorphous rights to future pension benefits. However, it will be easier to transfer WVP plans without embedded solidarity buffers when switching employers, while workers switching jobs within a sector will be able to keep the same plan.

Today’s corporate pension funds tend to favor the WVP plans, while pension funds servicing industry sectors, such as healthcare and retail, are leaning toward NPC varieties, says van Hoogdalem, who sits on the boards of two pensions for dairy and housing association workers.

Gauging Risk Appetite

Another complicating factor in the reshuffle is understanding the risk tolerances of participants. The proposed legislation imposes a duty-of-care responsibility on pension funds that will entail researching participants’ risk preferences, according to Patrick Heisen, a partner at consultancy PwC in the Netherlands who advises pension funds.

Today, defined-benefit plans typically use asset-liability-management studies and portfolio optimization techniques based on the risk appetite and capacity of the pension fund to design investment policies and set up the investment funds.

“Now they’ll need to make sure these steps of the institutional investment process also take into account the individual risk preferences of the participants,” he adds.

Reiniera Van der Feltz, Executive Governing Board Member at SBZ Pensioen, a pension fund for employees in the financial-services sector, said her team has already started talking to third-party firms about how to gauge the risk appetite of plan participants. She anticipates choosing one soon and to begin working with social partners to develop questions to gauge risk appetite.

Roest at ABN Amro said he instead sees the risk appetites of the pension fund’s 100,000 members as a later step in the implementation phase. He added that his team is initially focusing on understanding what the legislation offers and analyzing what it means for employees of various age groups.

Today’s defined-benefit plans leave investment decisions to the pension-fund boards, with some allowing interest-rate hedges on 70% of the plan’s liabilities and others just 30%, van Hoogdalem said.

Such a wide disparity conflicts with most boards’ claim to not speculate on interest-rate movements, she says. In the new scheme, hedging will largely depend on the risk appetites of each pension plan’s participants, highlighting the importance of regularly assessing those appetites. “You might expect older participants to prefer more interest-rate hedges to reduce interest rate sensitivity, although that offers less protection against inflation,” says Eric Huizing, chief investment officer at Dutch grocery-retail company Ahold Delhaize’s pension.

The Deloitte report goes as far as to suggest that this “could lead to eliminating the interest-rate risk protection for the 25 to 40 age cohort altogether, if the chosen risk behavior allows.”

NPC plans will have the automatic solidarity-buffer hedge. And since fund managers are choosing investment strategies for the collective group, they may be able to employ swaps or less volatile illiquid investments more easily to hedge interest-rate risk for older participants.

In the Mail

To evaluate risk appetite, pensions must first contact participants—easier said than done. Today, most Dutch pay little attention to their pension statements until they approach retirement.

“We realize that we, as pension funds, are not the most interesting channel,” Van der Feltz said. “We’re in contact with the communication and human resource departments of their employers, and we try to communicate through them, because pensions are a part of the whole benefits package.”

Pensioners nearing or in retirement are understandably more interested in how their plans are performing and engaging with them, and SBZ already communicates with them directly. But the pension fund also must find and communicate with ex-employees who now work for different companies but are still entitled to benefits.

Over the past decade, defined-benefit plans have not been indexed to inflation to cover cost of living increases. In addition, historically low interest rates may force some pension funds to raise premiums and/or lower payouts.

The new scheme addresses both those issues by creating a more direct link between financial market fluctuations and the pensions, creating greater transparency for the participants.

“The downside is that their pensions can go down quicker. I don’t think many participants are aware of that yet,” says Renate Pijst, director at Ahold Delhaize pension.

The move away from collective rights to participants owning the assets in their accounts may also be attractive, especially to younger participants who often switch jobs and even industries more frequently.

Ahold Delhaize Pensioen noted that pension funds will have to walk a fine line, however, since WVP plans will offer investment strategies of different risk-and-return levels. “We don’t want to encourage them to behave like traders,” Pijst said. Pension funds will also need to ensure that their new portfolios and policies are in line with things like environmental, social and governance (ESG) preferences.

Individual Dutch pension holders tend to be heavily influenced by their concerns for the environment and proactive as shareholders in engaging in decisions related to climate risk mitigation. Fund managers can comply with those ESG considerations because shares can be recalled by individual shareholders for voting. But asset managers may need to incorporate new workflows into their securities lending programs and collateral management chains to achieve consistency between their ESG policies and securities lending programs.

There is also a growing requirement in many jurisdictions for pension fund managers to evidence how they are executing on their fiduciary duties, which now need to embed financial and non-financial ESG factors, as well as the duty to generate revenue.

“We believe that younger pension investors will expect a combination of these fiduciary duties to be exercised going forward and they will hold fund managers to account on ESG matters, with climate being their primary area of concern,” says Ina Budh-Raja, Head of ESG Product Strategy in EMEA for Securities Finance & Markets at BNY Mellon. “Social inequality and diversity and inclusion are also areas of increasing focus for the new generation of investors.”

A Big Shift

While much planning depends on the shape of the final legislation, there are significant steps Dutch pension funds are already considering. One of the big challenges, Pijst says, is transitioning collectively invested assets to the new individual accounts (see Figure 5).

Pension boards will have to consider how to balance the interests of their members across all age groups, particularly because of the abolishment of the so-called “average premium system” in which all participants contribute the same, regardless of their age. The social partners will have to lay out how they will deal with such issues in a transition plan they must present to the regulator for approval.

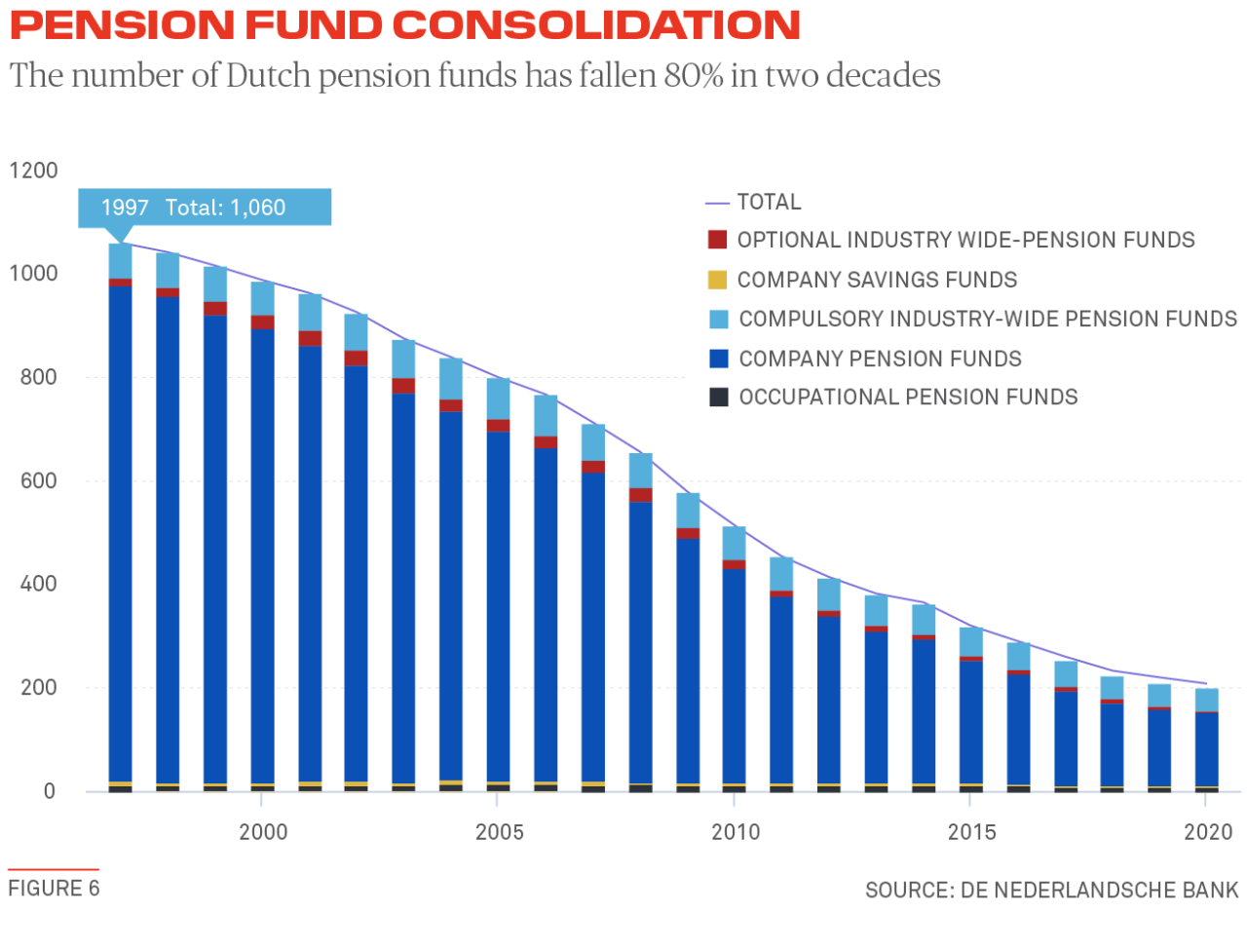

“A lot of [defined-benefit] pension boards will have to educate themselves on life-cycle investing, since this can be quite new for [them],” explains Marijn Jansen, an investment-solutions specialist at Achmea Investment Management, a division of the Dutch insurance group Achmea. It is expected that the shift to DC plans and related complexity will force various schemes to reconsider their future, driving further consolidation in the market, like we are seeing in the U.K. and other parts of the world (see Figure 6).

For WVP and NPC plans, pension boards must divide participants according to their age and risk attitude and provide a range of appropriate investment strategies. Since the lifecycle issue is similar for both types of plans, Jansen noted, pension boards can educate themselves about life-cycle investing and make significant headway before the legislation is finalized.

Unilever has one of the oldest pension funds in the Netherlands, serving almost 20,000 participants. It has been closed since 2015, but the company has another much smaller pension fund, Forward, that was founded in 2015 for the Dutch employees who are active at Unilever. That fund must be transferred into a new plan, although it is too early to say whether it will change into a more personal WVP plan or a more collective NPC plan.

“We have to determine whether it is appropriate to operate two frameworks, since it will require extra communication, administration and cost,” said Hedda Renooij, at Unilever APF, who oversees €6 billion in assets for around 24,000 participants. She added that stakeholders, including the pension fund and social partners, have started to hold monthly roundtables to discuss the path ahead.

Another issue will be transferring illiquid assets, since they are difficult to value daily and divvy up among defined-contribution accounts, compared to listed investments whose net asset values (NAVs) are readily available. They may have to be held in flexible, balanced funds similar to defined-benefit pensions’ approach today, Jansen says, so the pension fund can make payments with incoming premiums or by selling liquid assets.

Jansen said his team is also starting to talk to pension funds about how their specific participant demographics may impact asset allocations. Those with younger participants, he noted, will likely shift away somewhat from fixed income to assets providing more risk and greater potential return.

“Under the new regime, many pension funds will probably show less demand for fixed-income assets at the longer-end of the yield curve, particularly those with a younger plan participants,” Jansen said.

Dutch fintech firm Hyfen is seeking to facilitate the interaction between pension funds, their third-party providers and pension members via a platform that aims to connect these parties, while complying with regulations for personal data processing. Currently, it is focusing on developing software to explain to individual plan participants how switching to the new system will impact them.

“It's clear that the winning model will be very digital, based on customer intimacy and low cost,” said Hidde Terpoorten, CEO of Hyfen. “Paper-based processes and statements all need to go away so that we can service pension contracts and better help pension members in the future.”

“The shift will most likely result in different operating models for pensions that need to be serviced, so service providers like us are adapting their value proposition from front to back.”

— Marvin Vervaart, BNY Mellon

What Lies Ahead

Most pension funds probably won’t begin actual changes to technology systems and policies and procedures in earnest until a more definitive version of the legislation emerges. And then the clock will begin ticking to implement and test them.

“We’re going to face different dynamics that cater to the individual pension pots,” said Hulshoff at APG AM. “This will lead to new approaches to strategic asset management and duty of care, but also more information, insights and performance measurements when people start asking why their returns aren’t better.”

The transition should thus offer third parties currently servicing Dutch pensions, as well as newcomers, significant opportunities as well as risk. BNY Mellon services more than 30% of total Dutch pension assets, including custodial and related services such as investment accounting, performance measurement and risk analytics. The bank notes that it is imperative to understand as early as possible the new pension-plan structures and the market opportunities and threats, such as new product offerings as well as competitors.

Third parties must also research which type of plan clients’ constituents will choose and the required operating models and value propositions, and they should devise marketing campaigns to promote the new offerings.

“The shift will most likely result in different operating models for pensions that need to be serviced, so service providers like us are adapting their value proposition from front to back,” says Marvin Vervaart, a client solutions specialist for pension funds at BNY Mellon.

Given the challenges pension funds face, the delay will be helpful to many, especially in terms of educating constituents about why it is necessary to transition and communicating the new plans’ benefits and participants’ new dynamic role. However, the pushback so far suggests pensions have a steep slope to climb, along with developing new data streams and digital interfaces to provide account transparency to their members.

A downside to the delay is that it will be another year before pensions can understand properly the details of how to transition the assets, overhaul systems and build portals for savers to view their retirement money.

Addressing those challenges will mean taking advantage of all possible resources and expertise.

As Dutch pension funds prepare to transition, they must work closely with partners who have relevant experience, including custodians, asset managers and other third parties such as technology firms, said Frans Weijdener, a managing partner at Equitem Groep B.V., which advises on complex changes in the asset-management business.

“Firms need to understand their desired operating model first, before leveraging the expertise of strategic partners who can identify the key implications of the regulations and all the options,” Weijdener said.

John Hintze is a freelance writer for Aerial View Magazine in New Jersey.

Questions or Comments?

Contact dennis.presburg@bnymellon.com in Asset Servicing, ingrid.garin@bnymellon.com in Markets, or reach out to your usual relationship manager.